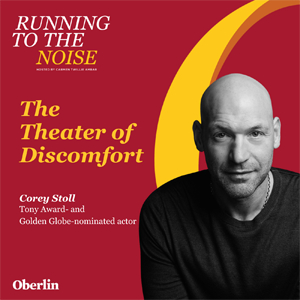

Running to the Noise, Episode 11

The Theater of Discomfort with Corey Stoll

Whether it’s a morally-ambiguous politician like Peter Russo in House of Cards, the Marvel villain Yellowjacket, or the ghost of Ernest Hemingway, for actor Corey Stoll, it all starts with finding truth in the script.

Stoll began his acting education somewhat reluctantly in fifth grade, but he hit his stride at the legendary New York performing arts high school LaGuardia — the Fame school. Rather than following in the footsteps of his classmates, like future co-star Sarah Paulson, Stoll opted to further his education and enrolled at Oberlin College and Conservatory where he studied interdisciplinary performance.

From his freshman year at Oberlin, Stoll was dazzling audiences and earning rave reviews for his performances in school and student-led productions. He even began his own theater company while at Oberlin with a few friends.

His most recent Broadway role of Bo in Appropriate — Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ Tony Award-winning play centered around an Arkansas family reckoning with their racist roots — earned Stoll a Tony Award nomination.

Stoll sits down with host and Oberlin College and Conservatory President Carmen Twillie Ambar to discuss his development as an actor, taking on complex and challenging roles, and how plays like Appropriate confront the systemic issue of racism.

Listen Now

[00:00:00] Carmen: I'm Carmen Twillie Ambar, president of Oberlin College and Conservatory. And welcome to Running to the Noise, where I speak with all sorts of folks who are taking on some of our toughest problems and working to spark positive change around the world and on our campus. Because here at Oberlin, we don't shy away from the challenging situations that threaten to divide us. We run towards them.

[00:00:46] Bo: Do you remember dropping me off in New Haven my freshman year? Mom was so sick she couldn't leave the car, so you stayed with her?

[00:00:55] Toni: Yes.

[00:00:55] Bo: Well, we showed up at my quad that I'm sharing with three other guys, and one of my roommates was this black kid from Philly, Clarence Montgomery, bright, nice guy. The quad was split into two bedrooms, two guys each bunking up. And for whatever reason, we were the last to arrive. The only bed left was with Clarence.

And while you and mom sat in the car, Daddy and I set about unpacking. And the entire time, he wouldn't look Clarence in the face. I don't know if it was because he was uncomfortable or what, but he shook every hand in that room but Clarence's. I remember thinking, “This is so weird.” Even afterwards, Clarence came up to me, asked me about it, “What's wrong with your pops?”

[00:01:37] Toni: Daddy's discomfort around your college roommate is not the same with…

[00:01:40] Bo: And the same thing happened with Rachel's parents at our wedding. I had completely forgotten about it till then. You remember how small that ceremony was? It was like they weren't even there. I had to tell them he was shy.

[00:01:51] Toni: But he was shy!

[00:01:52] Bo: You know what I mean. They still talk about it, you know.

[00:01:55] Toni: Bo, it was a different time. Things were still so new. He was uncomfortable. So what? It's not the same thing as harboring some secret hatred.

[00:02:13] Bo: But how do we know?

[00:02:16] Carmen: That was Corey Stoll, with co-star, Sarah Paulson, in the Tony Award-winning Appropriate, the play by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins centers around the lives of three estranged siblings who return to the ramshackle plantation home of their recently deceased father. Appropriate earned two Tony’s — Best Revival and Best Actress for Sarah Paulson. Critics called it a “brilliant, blistering, outrageous play with a wicked tongue” and praised Stoll's performance as “excellent.” He played Bo, a middle child in a family reckoning with its racist roots. The role challenged him like no other and earned him a Tony nomination.

Not everyone can move so seamlessly between theater, film, and television, and yet Stoll does just that. His previous roles include Ernest Hemingway in Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris, Congressman Peter Russo on the Netflix series House of Cards, business titan Michael Prince on Showtime's Billions, not to mention the villain Yellowjacket of the Marvel Universe. All the same, Stoll has always felt at home on the stage.

Before launching his illustrious career, Stoll studied interdisciplinary performance at Oberlin College and starred in a wide array of productions earning early accolades. I spoke with him before Appropriate closed its celebrated Broadway run at the end of June.

Well, welcome, Corey, to my little podcast. How are you?

[00:03:48] Corey: I'm great. How are you doing?

[00:03:50] Carmen: I’m good. So, I guess, I wanted to know a little bit about your background and, kind of, how you came to Oberlin, because, you know, I think some people know that you are, kind of, in what we call the Fame school for those of us who are old. I don't know if anybody else knows that anymore.

[00:04:06] Corey: Yeah. I don't know if this reference works. I used to use it as reference forever, and now I don’t know. It's, sort of, it’s dated, definitely.

[00:04:11] Carmen: Yeah, I don't think anybody knows what it is. But really, you know, for gifted performers, one of those high schools, that really, you know, brings gifted performers all together. And I guess I'm wondering, what made you leave New York to come to Oberlin, since you were in the, kind of, mecca of what people consider the space and place for performers?

[00:04:33] Corey: I discovered theater, sort of, it was, sort of, forced on me in fifth grade. There was, like, this big program from the Metropolitan Opera where they would have the students break into groups. Some people would be writers. Some people would design the sets. And, and some people would be actors. And I thought I wanted to do anything but be an actor. And I remember the teacher, somehow, I didn't think of myself as a class clown, or, as particularly outgoing, but I think she saw something in me. And I did this audition and got a big laugh and I've, sort of, hooked ever since. And, and then there was a teacher in junior high school who had, sort of, figured out the exact formula of how to get kids into LaGuardia, which was the high school for performing arts.

And by the time I was a freshman in high school, I remember, like, somebody asking me, “do you want to be an actor?” And very obnoxiously, I said, “No, I am an actor.” It was very pretentious. But I do think that whatever it was that gave me that arrogance or confidence at that age did serve me well, because I didn't feel that I had to prove myself. I felt that there was something about acting that touched something inside me and, and all I had to do was say that that's what I was and nobody had to give me a job for me to take that identity on myself.

And then, through high school, I… you know, my love for performing grew deeper, and it was this place where I could, you know, express my whole self. And I think especially during those really difficult, very hormonal years, and where you don't, you're just, sort of, forming your personality, to have a place where my whole self and the ugliest parts of myself, there was a place for that to be transformed into something meaningful to other people and that, that could be a connection with other people and that, in that connection, I could, sort of, transform that into something beautiful.

[00:06:32] Carmen: Did you feel that even when you're that age, like, you could still feel that kind of transference of a feeling, a connection with the audience? Like you already felt that even at the early stages?

[00:06:43] Corey: Definitely. You know, I think, in real life, as a teenager, when you are vulnerable, when you cry or you get angry, you don't really get much out of that, you know. That's usually a cost, you know. That's something that, that can be embarrassing, that's something that can be alienating.

But if you're able to be vulnerable on stage, in character, there's some real social currency in that in some ways. You know, that's a very, sort of, transactional way of looking at it. But it's a way to have your whole self be seen and loved.

[00:07:15] Carmen: Yeah, understood, appreciated and valued.

[00:07:19] Corey: Yeah, exactly. With the mask of the character, with the, sort of, that distance and that, sort of, safety. You know, I, I, personally, at the time, was… I was suffering from, really, profound depression. And I was really struggling with my weight. I was about 320-something pounds by the end of high school. So, even though I had this outlet, I was still, sort of, struggling in my own way. And I think, you know, when it came time for school to end, there were some people, you know, Sarah Paulson, who I'm doing this play with.

[00:07:51] Carmen: Yeah, you just did Appropriate with.

[00:07:53] Corey: Yeah, she was a year ahead of me at LaGuardia, and she went straight Into her career, you know. And that was something that, that was definitely an option for me, but I, you know, I came from this family where education was so valued. And it wasn't like I was, I didn't feel forced into it. It was just, I grew up hearing stories of college and it just seemed like this unique special time in your life where you can really dedicate yourself to learning.

So, I visited Oberlin and really fell in love with it. And I, I never regretted going there for a second. Every year, it seemed more and more clear that that was the perfect place for me.

[00:08:31] Carmen: That's so great. So, I'm going to take you back. We went back and went to the Oberlin Review to see some of your reviews from your time at Oberlin.

[00:08:38] Corey: Oh, Jesus.

[00:08:42] Carmen: So, I don’t know if you remember the production of Our Country's Good. They described it as “shining, an unconventional play requiring 10 of the 12 actors to play two roles.” And here's their review of you.

“First year student, Corey Stoll, shines. Those who thought his debut in Oberlin's Marisol was a fluke, should go to see him in this production. He brings much bubbling energy to the stage.” So, already showing your, you know, I know you were a Tony nominated actor in Appropriate. Already showing it at Oberlin in your first year here. Any memories of your, your time on stage at Oberlin?

[00:09:17] Corey: Oh, yeah. Of course. Yeah. I mean, that production of Our Country’s Good, I thought it was just incredible. It's a beautiful play. Very difficult material and, you know, very funny, but also very heartbreaking. And also, yeah, I did that. That was my first year. And also we did this production of Dancing at Lughnasa set my freshman year, which was really beautiful.

And then as I went on, I think I was was less interested in the main stage shows and the, sort of, official plays and I was more interested in the self-generated, if that was a Broadway at Oberlin, then I sort of really got interested in the off-Broadway stuff.

[00:09:49] Carmen: So, for those of you who are listening, you know, we have a rich theater program here. And main stage is really the productions that come out of the academic departments, but there are all sorts of student generating productions that happen on our campus all the time in all sorts of spaces and places.

And you're going to get the eclectic and the interesting and the offbeat and the, let me try to figure this out, but it's oftentimes plays that are written by students, and it's a really interesting space for exploration, I think, on this campus that I find really, really fun. So, I'm glad that you maneuvered over to the off-Broadway of Oberlin, so to speak, when you were here.

[00:10:26] Corey: Exactly. Yeah. I feel that, you know, those students who are self-generating, who are, you know, excited to take big swings and not afraid to, sort of, fail, I feel like Oberlin really nurtured that. And then, by a group of friends, we started our own, sort of, theater company and said, like, you know, what plays do we want to do? And, you know, the budget's going to be a lot smaller. We're going to have to, sort of, find our performing spaces. But that sort of can-do attitude and that sort of sense of just, sort of, “Let's just throw it against the wall and see what sticks.

[00:11:01] Carmen: So, one of the things that I think a lot of people admire about your career is just it's diversity, not only in genres, but theater, television, movies, you know, lots of people know you from House of Cards and other things. But you've always said, at least all the reads that I've done about you, that your best work is in the theater.

And I'm wondering, you know, for those of us who loved you in all these other things we've seen you in, we spent a lot of time in the prep for this talking about House of Cards, because that's the first time that you kind of came to my consciousness in terms of knowing you. Well, before I was here at Oberlin, so I didn't know you in the connection with Oberlin. Why do you think of theater as your best work? What about it for you says, “Oh, this is when I'm really at my best?”

[00:11:44] Corey: I think there's a couple of reasons. I think theater is the only acting, I mean, it's the only genre where the actor is really the primary controlling factor, you know, at any given moment. The more film and television that I do, the more that I realized that my job on a film set is to supply the raw materials for the director and the editor to create the performance.

[00:12:08] Carmen: Oh, interesting. The performance is being curated by someone else. Is that how you would describe it?

[00:12:14] Corey: Yeah. And it's even more than curated. It's really being created. The, you know, what, what you can do with editing and music and, you know, color timing and, you know, where the focus is at any given moment is really, it's a really profoundly powerful thing that the post-production people have, they have control.

And there's a lot that actors bring. You know, obviously, when you're on stage, you are completely in control of how long you pause at this moment or how fast, you know. And then from night to night, if that first scene came on really particularly hot, you can make those adjustments as you go on. And then, all these things have meaning to an audience. And so, when you're an actor in theater, you are right at the center of all these artistic decisions.

And so, I can't be a judge of whether my work is better in any particular place, because it's impossible for me to judge that. But in terms of the feeling that I have of control and being at the center of what's happening artistically, there's nothing that can beat theater in terms of that.

[00:13:26] Carmen: So, I know you for this. Maybe other folks have different perspectives on some of your key characters that we really know you for, but you've played a lot of what I would call a morally ambiguous characters, you know, the Congressman Peter Russo that people know you from House of Cards. And you've played Iago and Othello. You’ve played the Yellowjacket in Marvel. But I guess, and even this character that play in Appropriate, I haven't seen the show, but one of our staff members went up to see it several days ago and just raved about it.

Tell us about how you prepare for roles, particularly, the roles that have all this complexity in it, all of this kind of angst and lack of clarity. Give us a sense, you know, for the students who are out there thinking about, “Now, how do I prepare for interesting and wonderful roles?” Give people a kind of a sense of what your process is.

[00:14:19] Corey: Yeah. I mean, the process is different for every project. You know, there's certain things require more research than others. And so, in certain things, there's just the research is, sort of, more fun and compelling than others. You know, when I got to play Hemingway, it was just an incredible opportunity to just read all of Hemingway. And that was just a pleasurable thing to do. And certainly, when you're doing Shakespeare, there's just an enormous amount of very… it's just, you know, grunt work of just figuring out exactly what everything means.

[00:14:52] Carmen: I was going to say, “What does this actually mean?

[00:14:54] Corey: Yeah. And that's essential. Like, you can't fake it. You can't, sort of, know what you're saying. You really have to know exactly what you're saying at every minute, not that the audience is going to get it, you know. When you're doing Shakespeare, you have to assume that the audience is going to, maybe, understand a third of what you're saying. And that, and that is your job to find out what those keywords are that are going to pop out, that will give them the basic sense of what's happening, and that the other stuff, you hope, is just happening on a subliminal level.

But, with this play, you know, it really starts with the text and with the words and feeling how truthful they are to say. You know, I have this big toolkit that I've built up from years and years of training and experience. And in general, I like to not pull them out until I need them. So, if I can just pick up a script and say the words and it feels truthful, then I, kind of, want to go with that, until I'm doing the scene and, and I feel like I'm missing something or something feels not truthful. Then, I say, “Okay, let me take… let me go back and say, ‘what am I not thinking about this character's history or what, you know, or, what are assumptions I'm making about this character that don't have to be true?’” And then I can start to break it apart.

[00:16:18] Carmen: And so, it's not that you go into it with full backstories that you've created sometimes for these characters. You're not… that's not how you kind of operate.

[00:16:25] Corey: I don't do that because I feel like it's, kind of, put in the cart before the horse. Like, you know, like, I feel like the truth of the character, if the writing is good, the truth of the character should emerge from just a cold read on a certain level. And then, as I start to feel the character, start to embody the character, then I can start to make some actually informed choices about my family history, my education, you know, my psychological preferences or fears.

And so, the two things, sort of, have to happen in concert. But every time I've tried to, sort of, show up to a process where I've made all the decisions about who this character is, it's a little arbitrary and it's a little, you know… and then, I'm trying to have to fit the words to fit what the decisions I've made about the character. Whereas, they really, sort of, have to happen in concert.

I'm very lucky to have started with, like, real acting training from a very young age. What is the action? What am I doing from moment to moment? I did that work very deliberately. We were forced to do that in high school. And by the time I was in Oberlin, that stuff was really much more instinctual. And I would occasionally have to, sort of, stop and be like, “Hold on a second, what am I trying to accomplish? What do I want from this other character,” you know, as a, sort of, a diagnostic tool or a way to, sort of, like, make sure that my work is truthful. But I'd say, nine times out of ten, the best choice is going to be made instinctually.

[00:18:06] Carmen: You know, I want to make sure that the audience gets a little bit of the backstory of Appropriate. And one of the reasons why we wanted to talk to you about it is just because, you know, this issue of race and, sort of, understanding how we relate to each other in the context of race and antisemitism, and this is one of the themes of this play. So, maybe, if you could just help the audience, if they haven't had a chance to see it, kind of, you know, just a little bit of the quick summary of the play and, maybe, a little bit about the character, Bo. Like, who is he and what's really his motivation in this play.

[00:18:39] Corey: Yeah, the play, you know, follows very similar lines, familiar lines of a lot of great American family plays, you know, like, August: Osage County or Long Day's Journey Into Night or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, a lot of Sam Shepard stuff. It’s the Lafayette family, we were a family of three siblings. The mother died relatively young. We grew up in D.C. We had family roots in Arkansas.

[00:19:07] Carmen: Yeah. I'm from Arkansas, everybody, just so I'm from Little Rock. I was born and raised in Little Rock, so there you go.

[00:19:13] Corey: This is, this is, I mean, this is like the sticks in Arkansas, where we are. That's it. I think Little Rock is like, that's the, you're a city girl.

[00:19:21] Carmen: Yeah. We're city girl, absolutely.

[00:19:23] Corey: But that's not, you know… my character, Bo, that's not his experience at all. He grew up in D.C. but the family was always from there. And then after me and my older sister went to college, our father moved back to Arkansas, took our younger brother with him, and moved into the family plantation, which was in, in disrepair. And then our younger brother, who was a drug addict and an alcoholic, he left town under a scandal, and we haven't seen him for 10 years.

Our father died. Me and my sister are back at the house, ready to sell everything. And then our younger brother shows up, just at the last minute, you know, when it's time to sell it. And so, it's already a situation of great conflict between the siblings about dividing this estate. And the estate is, it's in shambles. We're not going to make any money. You know, we're under financial stress when we find… first, we find this book of photographs of postcards and photos of lynchings, this huge book with, you know, all these really horrific images.

[00:20:35] Carmen: Graphic, sort of, images of lynches.

[00:20:36] Corey: Yeah, which were apparently very common in the early 20th century. I think I read that postcards of lynchings was actually at the, for a period, the most common thing sent in the U.S. mail.

[00:20:48] Carmen: Yes, that's right. As kind of images of fun, right, because people would go out in a celebratory way to these lynchings. It's kind of a party, a picnic, an enjoyable way to spend the afternoon, so to speak.

[00:21:02] Corey: Right. And so, we're, sort of, confronted with this, but we're still really not dealing with it as a family. I mean, even though we know that the family home, it was a plantation. We know that slavery is part of our inheritance. To see that it's as close as our father, this racism, and it's really a, sort of, a dance of denial, different levels of denial that we all have as, you know, as, as siblings. The thing I think is really, really brilliant about the play, the playwright, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, is black. Everybody in this play is white.

[00:21:39] Carmen: Well, I think that's one of the things that's interesting about it, because oftentimes, when you're discussing race, it's sitting around a black family responding. What's interesting about this play is that it's a white family trying to grapple with it in these interesting ways. I think that's one of the things that makes it so interesting, a look.

[00:21:58] Corey: Yeah, yeah. And I think Branden… he has, it's both, so, I think, some of the most biting acid, sort of, you know, looks at these characters and their blind spots, their willful blindness, and their entitlement. But also, there is this incredible empathy that runs through this play. And a lot of what is the most exciting, sort of, pleasurable parts about playing this character is to feel the audience's allegiance swinging wildly.

[00:22:31] Carmen: Yeah. I've read that you said that you're watching the audience. There's sometimes for Bo, wait, wait a minute, what's going on there? Sometimes, for this character, “Oh, my, no, no, they're not right anymore.” Like the, you know, they're moving through this up-and-down view of who is in the right here.

[00:22:46] Corey: Yeah, and we all have this great psychological need to make people either good or bad and to make ourselves good. And I think what this play does so brilliantly is that it's… everybody in the audience is having their own individual reaction to everything. And then, they're reacting to how the audience is reacting to everything. So, it's just… there's just a lot of friction happening on stage every night.

[00:23:13] Carmen: You know, I'm wondering, as you're talking about this, what you think this play brings to the conversation about America's race consciousness, about race in America, like, because you said two things that struck out to me in that conversation. One, we're moving back and forth. We're trying to find who's good. We always want to see the goodness in ourselves, right? That's a need that we have. And as I think about this issue that we are still grappling with around race in this country, I'm wondering what you think this play does to that conversation, as you imagine it, by the time the play is over.

[00:23:47] Corey: You know, it's funny. I mean, it's… and my, I don't think my opinion is any more valid than anybody else who comes to the play, sees the play. And I think, I think that's, sort of, the power of the play is that everybody has their own journey through this and their own set of defenses that they need to encounter.

I think this play's a lot about shame. And there's so much shame around race. And what do you do with shame? Is shame a completely useless emotion? Because on a certain level, shame is so painful, that you just want to turn away from it. So, we encounter these truths about our history.

And, you know, and, and of course, my defenses were… are just as up as anybody else's. You know, I, I read this play and it was just like, oh, you know, I'm Ashkenazi Jew. My family came into this country in the late 1800s. So, I was like, “Okay, so this is not my crime.”You know what I mean? It's not my family.

[00:24:47] Carmen: That’s right.

[00:24:48] Corey: But of course, that's really simplistic and letting myself off the hook because, you know, I code as white and I have the privileges as a white person and who knows… and if you went back in time, in my family, you know, there's a crime in, in everybody's family. So, instead of deflecting that and saying, “Okay, well, I'm not, you know, I'm not a direct inheritor of slave-derived wealth…”

[00:25:13] Carmen: Right.

[00:25:14] Corey: “I’m obviously an incredible inheritor of the benefits from that, you know.” And okay, so take that as a given, what do I do with that?

[00:25:26] Carmen: Let me just say, if you answer this question well, Corey, you get the, you get the gold star. I just want you to know, everyone's hanging on you, how you answer this. What do we do with this? This is it.

[00:25:37] Corey: Well, I mean, but that's, but, but unfortunately, you know, unfortunately, there is no easy answer with that.

[00:25:41] Carmen: There is no easy answer, absolutely.

[00:25:41] Corey: I mean, I, but I, but I do think the answer is that we don't do two things. One, we don't ignore it.

[00:25:49] Carmen: Okay.

[00:25:50] Corey: And, you know, pretend like America is, and has always been, this perfect place. But we also don't get so swallowed up with shame and white guilt, which is just paralyzing, that, basically, the same thing happens and nothing… things can't move.

[00:26:12] Carmen: That’s right. You know, lots of people know I'm an African American woman. I think, on the white guilt framing, and we can't do anything about it, and so, we just are paralyzed, I think the same is true about the notion of feeling like a victim and being victimized and being paralyzed by victimization and then not able to do anything about it. Like, you have some obligations, too, to go, “Yeah, okay, I get it, but what's the next thing? Like, I can't sit there either, right?”

I mean, I think it's all of us choosing not to just sit there in these things that are paralyzing, these things that seem like they are no way through. And everybody choosing not just to sit there is part of what you're admonishing us in the first part of your statement, which is that you got to go and do, right? You can't just sit in these paralyzing states.

[00:26:58] Corey: Yeah. And not to use shame to deflect the opportunity to look at these very uncomfortable truths. This is why I'm an actor and an artist and not an essayist or political thinker, because I think I can attempt to embody these stories, and that these thoughts can occur in the audience's mind. But I think with a truly great play like this, I think it really is, that it's not… you know, the play, it isn't an algorithm. You can't, like, boil it down to a point. What the play has to bring is the experience of going through this with other people.

[00:27:43] Carmen: Yeah. You know, it's interesting, it's funny because, as I was preparing for this conversation, I was talking to the team about why I love shows. And I talked about that kind of feeling that you get as an audience member when you're going through something together. You're going through something different, though, because each person is having their different experience, and yet, we're having a collective experience. And I'm imagining that this play, too, helps all of us, kind of, take that reflection moment. It's not an algorithm, because your reflection is different than mine, right? And yet, the decision to reflect, to ponder, ask yourself questions, is one of the most beautiful things about art, just in general. It forces you to ask questions. And hopefully, by asking those questions, you choose to be different and do things differently.

Last question, what is your version of running to the noise? What would you say if someone says, you know, when Corey's running to the noise, he is… doing what?

[00:28:44] Corey: I think, in my artistic life, in my career, I have always prided myself on choosing roles that frighten me. It’s a spoiler alert for the end of this play, but the very last moment with any person on the stage is, you know, my, my character who seems to be completely, sort of, impervious to a lot of the, the drama on the stage, in the stage directions, you know, I go to leave the house, you know, after our family has really fallen apart and all this drama has happened, and I touch the doorknob, and I… you know, it says that he, he breaks down in sobs, and he sobs and sobs and sobs and sobs, and then he sobs some more. Those are, like, that's literally what Branden Jacobs said. That’s literally what he said, which is just, like, as an actor, you know, to go from 0 to 60 every night is… I never encountered such an insanely impossible stage direction to follow.

But then I remember, like, reading it and being like, “I can't. I can't not take up that challenge,” you know, because it's a great moment, and it works for the play. It's what the play needs. It's an incredibly audacious thing to ask an actor to do. But why would I pass up that opportunity to challenge myself? And I found a way to be able to do that. And I really had to pull a lot of things out of the toolbox to, sort of, figure out how to consistently and safely do that, you know, to, you know, protecting my own psyche.

And so, that's an example of the kinds of things that both repel and attract me when I read a script. And, you know, I really count myself as very lucky to have continually been challenged by very, very difficult roles. And I can't… you know, I do occasionally take on a part that I feel like I can do with my eyes closed. You know, I have to feed my family. But most of the time, when I take a role, it's the thing that I've never done before that I don't know if I can do that is exciting.

[00:30:50] Carmen: Well, I appreciate you taking your time to do this podcast. You know, I always love it when I get a chance to, kind of, sit in the seat for students a little bit. You know, I, oftentimes, say that everybody needs images to look to to know that what they want to achieve is possible. And I just have the pleasure of talking to all these Obies across the world who have done these incredible things. And I just want you to know that, that the students here admire your work, admire what you do, and we're awfully proud of you. So, thanks so much for being on Running to the Noise. We appreciate it.

[00:31:20] Corey: Yeah. Thank you so much.

[00:31:21] Carmen: Thank you.

[00:31:21] Corey: I'm very proud to be an Obie.

[00:31:25] Carmen: Thanks for listening to Running to the Noise, a podcast produced by Oberlin College and Conservatory and University FM, with music composed by Oberlin professor of Jazz Guitar, Bobby Ferrazza, and performed by the Oberlin Sonny Rollins Jazz Ensemble, a student group created to the support of the legendary jazz musician.

If you enjoyed the show, be sure to hit that Subscribe button, leave us a review, and share this episode online so Obies and other folks around the world can find this. I'm Carmen Twillie Ambar, and I'll be back soon with more innovative thinking for members of the Oberlin community on and off our campus.

Episode Links

Running to the Noise is a production of Oberlin College and Conservatory and is produced by University FM.