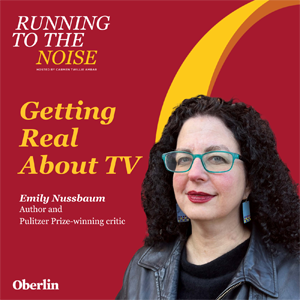

Running to the Noise, Episode 10

Getting Real About TV with Emily Nussbaum

For Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Emily Nussbaum ’88, it all started with a TV show called Buffy the Vampire Slayer. When the cult hit first aired in 1997, Nussbaum, then a literature doctoral student, watched it like anyone else. However, it was love at first bite: Buffy would consequently alter her entire career trajectory.

“I wanted to abandon the old method of you can only praise TV in the most condescending possible way, by sort of patting it on the head and saying, “Good for you, TV. You did something good.” I actually wanted to have high standards,” says Nussbaum.

With an English major and creative writing minor from Oberlin, Nussbaum has written for the New York Times, New York Magazine, and The New Yorker. Her latest book, Cue The Sun!: The Invention of Reality TV, chronicles the history of reality TV and explores the genre’s vast sociopolitical implications — from how The Apprentice led to Trump’s presidency to the questionable ethics of the dating show.

Ahead of the book’s June release, Nussbaum joined host and Oberlin College and Conservatory President Carmen Twillie Ambar to discuss reality TV’s complex history and its complicated role in our culture, and why Nussbaum fell in love with television.

Listen Now

[00:00:00] Carmen: I'm Carmen Twillie Ambar, president of Oberlin College and Conservatory. And welcome to Running to the Noise, where I speak with all sorts of folks who are taking on some of our toughest problems and working to spark positive change around the world and on our campus. Because here at Oberlin, we don't shy away from the challenging situations that threaten to divide us — we run towards them.

[00:00:45] Principal Flutie: Welcome to Sunnydale! A clean slate, Buffy – that's what you get here. What's past is past. We're not interested in what it says on a piece of paper, even if it says–

[00:00:57] Buffy: It wasn't that bad.

[00:00:58] Principal Flutie: … you burned down a gym!

[00:01:00] Buffy: I did. I really did. But you're not seeing the big picture here. I mean, that gym was full of vampire… asbestos.

[00:01:10] Carmen: If Emily Nussbaum had never seen an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, she might have been a professor of literature instead of a Pulitzer Prize-winning television critic for The New Yorker. But like an unscripted reality series, life threw her a curveball. It was 1997 and Nussbaum, then a literature doctoral student, took a break from reading her latest 900-page novel to turn the dial on an old-fashioned TV to the WB.

Like all first loves, she fell hard for the horror comedy about a high school cheerleader who flirted with boys and flunked her classes by day and stabbed vampires to the heart with pointy wooden stakes by night.

Nussbaum never finished that doctorate. She has written for Slate, and the New York Times, she also worked as an editor and writer at New York Magazine, where she created the Approval Matrix, a brainy, what's hot and what's not guide, to low brow and high brow culture, charting the brilliant and the despicable.

In 2016, she won the Pulitzer for what the jury called: “television reviews written with an affection that never blunts the shrewdness of her analysis or the easy authority of her writing.” Before The Sopranos and Succession, before the explosion of edgy programming on streaming services convinced haughty critics that television was worth watching, Nussbaum argued that TV was art, as worthy of rigorous critique as books or movies or paintings. And those who dismissed television as a vast wasteland were missing the point.

Critical contempt for television, she wrote, was like refusing to look in the mirror. With the release of her new book, Cue the Sun!, Nussbaum is once again swimming against the critical tide, bringing her sharp wit and discerning eyes to the study of a maligned, misunderstood, but hugely consequential genre, reality television. We can't wait to talk to her about that.

So, Emily, welcome to Running to the Noise. We are so happy to have you.

[00:03:09] Emily: Thank you for having me.

[00:03:10] Carmen: So, wow, there's so much to talk about. But I have to ask, what about your Oberlin experience prepared you for the stellar career you've had?

[00:03:21] Emily: Well, I had a great time at Oberlin. I made a lot of friends, I took a lot of wonderful classes. I was an English major with a creative writing minor. And I loved the creative writing department. And I can tell you about lots of things I did at Oberlin, but it's true that they don't have anything directly to do with journalism or… but the one thing I will say is that, when I was at Oberlin, I was actually obsessed with magazines. And so when I would go to the library, I don't know whether they're still there, but there were these amazing archives of all old copies of magazines at the time. And so, I would go and I would take, like, a big box of old Esquires or Ms. Magazines.

[00:03:58] Carmen: Mm hmm.

[00:03:59] Emily: Or I liked reading the poetry in the New Republic. I don't know what it was, but like, whatever the old magazines were, I would sort of obsessively read all of the old copies. So in that sense, I did a self-education in magazines because I thought magazines were a really fascinating platform and I liked a lot of the writing, I liked the design.

But what at Oberlin prepared me? Well, I'll tell you one thing. I have spent a lot of my career as a television critic. And a lot of times, people ask me, “When you were at Oberlin, did you want to be a television critic?” And I was like, “That makes no sense.” I went to Oberlin from 1984 to 1988, which is possibly the worst time in television in human history. I mean, not that there was nothing good on the air, but it wasn't a period that was going to inspire you to be like, “I really want to write about the shows on CBS,” in 1986 or whatever.

I pursued a lot of things in my 20s. I did a lot of temp work. I did writing, that was creative writing, and I did political activism work. So, I didn't actually get into journalism until I was around 29. And even then, I didn't really want to write criticism, because I think I thought criticism was mean. What I mainly wanted to do by the time I ended up writing was not criticism, it was I wanted to argue with people about television. And at that point, there was TV worth arguing about.

[00:05:14] Carmen: So, tell us why you fell in love with television and why you talk about it as an art form. And for those of you who are as old as I am, you'll remember an era where you know, actors and actresses would kind of, sort of, say, you know, if you have to go to television, like your career is over, like the kind of highbrow, look at artistic work was movies, maybe documentaries. But TV was, sort of, maybe not considered the best place for your career.

[00:05:43] Emily: Well, the period in which I got really interested in TV was a long time ago now, which is the end of the ’90s and the beginning of the, after the turn of the century. And it was the period when there was this real explosion in TV creativity. And as you're saying, television was historically viewed as less than other art forms. I mean, really not as an art form at all, but as a junk medium, which was at best a bad habit that was, kind of, a fun, yucky, but at worst, a kind of addiction and a toxin and really bad for you.

And so, there was a habit I found, even among TV critics who like television, in praising TV, and especially anyone outside the TV criticism world. It had to be constantly compared to books and movies, which were considered elevated media.

And so, part of my interest in writing about television was that there were a bunch of shows that I was very passionate about. And Buffy is the one I always pick as my primal show, because when it came out, I remember being especially startled and excited by it, because not only was it a brilliant, ambitious show, but it was also a show that didn't look like fancy stuff. It wasn't easily comparable to books or movies where you can say: “It transcends television!” No, it was television. It was an episodic show. It was a mixture of different genres. It was a teen show. It was a little bit of a gothic romance. It was a horror show.

[00:07:05] Carmen: Little comedy, yeah.

[00:07:05] Emily: It had sitcom elements. And it was junky-looking. It was made relatively low-budget. It was on a teen network. But it had what seemed to me to be all of these beautiful, ambitious, feminist, symbolic themes. Like, it was… and yet, it was not pretentious. And it kept getting more ambitious as the seasons went on.

And this was during a period when people would, when they talked about television and they wanted to praise it, they would talk about another show I absolutely adore, which is The Sopranos. But The Sopranos was considered impressive because The Sopranos transcended television. It was like a novel. It was like a movie.

[00:07:41] Carmen: Yeah, a serialized movie, yeah.

[00:07:42] Emily: This is my guiding force in wanting to talk about television, is I wanted to abandon the old method of you can only praise TV in the most condescending possible way, by sort of patting it on the head and saying, “Good for you, TV. You did something good.”

I actually wanted to have high standards. I like some things and I don't like other things. And I wanted to develop a critical rhetoric that praised television as television.

[00:08:06] Carmen: Well, let's make sure the audience knows. So your new book is called Cue the Sun! The Invention of Reality TV. So, there's so much to talk about. And the first question is, why the decision to write about reality TV? Like, what was the compelling reason to say, “Okay, we just need to spend some time on this aspect of television?”

[00:08:25] Emily: Well, there are two things about this. One of them is, I talk about this a bit at the beginning of the book, but I originally wanted to write this book long before I was writing TV criticism in 2003, when I was a freelance writer in New York. And a group of friends and I got together to talk about possible book ideas. And I suggested, I, at the time, I had watched a lot of The Real World, and I was watching the first season of Big Brother, which was streaming, which was so nerdy and eccentric that it was like an embarrassing thing to admit. And it was also a failed season.

So, anyway. But I was interested in this explosion of stuff like Survivor. And I said, “I want to write a book that's like a reported book about the reality world because it seems to have all these big characters.” It's really colorful. It's like a new Hollywood. It's like the beginning of Hollywood with all these shysters and entrepreneurs and kind of shady, shady, colorful characters. And my friend said, “You better write that fast.” So, his point was it’s a fad.

[00:09:19] Carmen: It's going to be a fad, yeah.

[00:09:20] Emily: It's a fad. it will be gone in two years, and if you try to write a book on it, it won't be worth it. So, I listened to that. But he was wrong, and it took 20 years. But by the time I got back to it, obviously, it was not a fad, it was an industry. And I wanted to write with this book something that's very different than what I had written before. I've never written a non-fiction reported history book. This is not my opinions about reality TV. And it's also not about all reality TV; it’s about the creation of reality TV. It runs from radio — 1947 through 2009. So, it basically runs from Candid Camera, Queen for a Day through the rise of Bravo and The Apprentice.

It basically traces: Where did this genre come from? And who made it? What does it mean? And how is it made? It's an attempt to write, sort of, the unwritten history of one of the most important genres out there, because there's, sort of, no denying that reality at this point is an incredibly important genre of art. But,it's often treated as a guilty pleasure, a triviality, something nobody has to be particularly thoughtful about.

And so, sometimes people have a finger wagging attitude toward it, and sometimes people have a fan-ish attitude. In this book, I was like, I did more than 300 interviews, and it's a book that is the stories of the people who created these shows and how, where they came from, on both sides of the camera, cast and crew.

[00:10:52] Carmen: So, we started a discussion about television and talking about it from the perspective of you saying, “This is an art form that people are, sort of, dismissive of. I want to make sure people understand that.” Would you say the same about reality television?

[00:11:04] Emily: 100%.

[00:11:05] Carmen: And you would describe it as an art form?

[00:11:07] Emily: Well, I mean, you know, it's tricky. The phrase, “art form,” is useful in some ways, but then it has this strange set of connotations as though saying something is an art form means it's important and it's valuable and it's elevated and there's a, sort of, highbrow lowbrow thing about it. That's just not something I'm concerned about with reality TV. What it is, I mean, whether you wanted to call it an art form or a craft or something, it's a genre on its own. It's not the same as sitcoms and drama. It has its own aesthetic history, its own ways of making things. And they are the result of, yeah, artists, like editors and producers who have skills and tools of creating these shows.

And, you know, obviously, reality is a very broad category. And I'll tell you the way I define it in the book so you understand what I mean. I basically refer to reality as “dirty documentary.”

So, to me, what reality is, or at least how I define it, is it's when you take documentary or cinéma vérité documentary, which I think most people think of as like a classy, quasi-journalistic, elevated.

[00:12:11] Carmen: Right, yes. When you say you've watched a documentary last night, people think that you've done something of value.

[00:12:17] Emily: Right. Historically, at least, it's been treated that way. It's sort of blurry nowadays. But anyway, when you take that and then you cut it with, mix it up with, something that's more aggressive, more commercial, serialized television format. And so, sometimes you mix it up with a game show. Sometimes you turn it into a prank show, as with Candid Camera. Sometimes you mix it together with a soap opera.

And that outside element helps heighten it and put more pressure on the people in it. So, instead of just having your camera sit around waiting for behavior, you're essentially getting the real people in, who are the subjects of your show, to react reliably and under pressure to form all sorts of different kinds of stories.

But the thing that I do think is consistent about it is that there is this titillating, fascinating, sometimes very ethically fraught, sometimes really beautiful kind of staging ground for human behavior. And that's why, despite the fact that, pretty much, every phase in reality TV has created a related moral crisis among viewers and critics who are appalled by it, it keeps people watching because people want to see themselves mirrored on screen.

And so, yeah, in this book, of course, it's, you know, it's a contrivance mixed with something real. And so, I trace, sort of, where that came from. And one of the arguments I make in this book is that those strains that I'm talking about, and it's actually four strains, because there's another one that I call the clip show that runs through like Cops and America's Funniest Home Videos. They're like short documentary clip kind of things. And, those become the Internet. Like, those become like YouTube and the internet.

[00:13:58] Carmen: That’s right.

[00:13:59] Emily: But the other three, the argument I make is that, essentially, what happened is that the game shows, the prank shows, and the soap operas all merged together around 2000 with Survivor. When Survivor came out, it was a global blockbuster, and it set off what was essentially a massive gold rush in production in Hollywood. And it created the modern industry. And Survivor succeeded for many reasons, including a very brilliant format. One of the main reasons, and it's the thing I've been leaving out of this whole discussion, was economics. Because these are shows that don't pay actors and don't pay writers. That's why they've always existed. That was why they've always been green-lighted. So, they were able to put Survivor on the air. It cost them nothing. It made billions of dollars and the world changed.

[00:14:47] Carmen: What would you say about the participants? Like, what role do they play in the creative process? You know, one of the things I think is interesting about your book is, over time, you know, when it first started out, the participants were maybe a little bit more naive. Now, by the time you get to reality TV at this era, like they understand exactly what they're signing up for — most of them — and they are part of the game, I think, part of the… you disagree?

[00:15:13] Emily: I do disagree. And part of the reason I disagree is that, just a few weeks ago, I published a piece on modern reality. It was about Love is Blind in The New Yorker. And I have to say, when I was working on that piece, I was pretty surprised because I had… you know, I do think that, obviously, people who go on reality shows now are aware of reality TV in a way that nobody on the first season of The Real World was.

[00:15:35] Carmen: Well, that's right. And that's my introduction. Like, The Real World, I'm in that era watching those kids on MTV, you know, turn off the light and talk into the camera, you know, in their private conversation where they either reveal something very deeply personal or they rip the roommate because they acted silly earlier in the day. So, that's kind of my first introduction to reality television.

[00:15:54] Emily: There's definitely, in this book, there's a kind of innocence and naivety that's both, you know, touching and powerful sometimes in performances on the air, and also makes people prone to exploitation that I cover, but I don't necessarily think that people who go on shows now actually do know what they're getting into. Some of them do. For one thing, the contracts people sign make it so that you'll never know what happened to them on those shows. Because they have to sign very intense NDAs that forbid them from complaining or talking about anything that happened to them on the show. And if they have real complaints, if they were exploited or abused, it goes into arbitration.

So, I think that the assumption people have that anything that happens to anybody in a reality show, well, they signed up for it, they deserve it, I think that anybody who actually cares about labor rights in the United States should open their heart a little more to the fact that people on both the casts and the crews of modern reality shows are basically just replicating the injustices that the whole thing began with, because there are many things to say about reality TV, but you cannot avoid the labor part of it which is the fact that it was created to rip people off.

[00:17:03] Carmen: Yeah. You know, you talk early on in the book about the things that they, and I think they still do, kind of, you know, putting something on a coffee table that people weren't expecting, and they kind of drop this thing, and everybody's kind of surprised by it, or they cut it in ways that people, you know, it's not really the truth. And I guess I'm assuming that if you are on a reality TV show at this point, you kind of know that's a possibility. You know that those things can happen. But you're saying that the culture of NDAs and this kind of approach to what it means to sign on means that you may not be as aware as you, as it may seem from the outside of what could be possible for you if you end up on one of these shows.

[00:17:42] Emily: Knowing something in theory is not the same as experiencing it in practice. If you're totally deprived of sleep, if you're cut off from the world, if you're becoming incredibly close to your skilled producer who knows everything about you from the psych test that you did to get on the show, if they're asking you highly personal questions, and if you're drunk, and if you fell in love and somebody told you that the other person was in love with you, like, there's a certain point at which you cannot control your behavior. And even if you do, and the production decides they don't like you, they can cut what you say, as you say, out of order, any way they want, and you'll never be able to complain about it.

So, I think that reality shows have trained people to have zero empathy for anybody who gets portrayed poorly on a reality show, because I think people blame and have historically blamed anybody who goes out in public, seems thirsty for attention, tell personal things that cross the line because people love to judge and feel superior to them. But I have to say, both from the work I did on this book and in my reporting on the Love is Blind thing, I mean, I'm not saying that everybody who goes on a reality show who has a bad experience is an innocent victim and that they're just crushed, but, you know, this is what I say in the Love is Blind thing. It's like Vegas. Like, you go in, you think you have a system, but the house always wins because they have all your footage.

So, the book that I wrote is about the origins of those traditions. And yes, what you were talking about were, you know, like, the producers learning how to either create a format that will squeeze people for powerful and interesting behavior or how the editors learn to do things like “Frankenbites,” which can cut people's language up and make it sound like they said something they never said. There's a whole continuum of shows. But this started out with you asking just about like the people who go on the shows. And I think that that fascination and contempt for public people who go on to television in this way does go back to the audience participation shows of, literally, on radio. People were already writing articles saying, “What has happened to American culture? Narcissists are going on television and telling personal stories about their families.”

Like there was this show, Queen for a Day. Women would go on. There was a panel of them. It was like a beauty pageant for who had the ugliest life. And everybody would compete. They would tell these stories in order to try to win a big prize, and the audience would clap and there was a clap-o-meter. So, it was considered a tawdry, exploitative show, and there's no doubt that it was. And also, it's a pretty sexist show. But at the same time, it was one of the only things on TV where women were talking about poverty, about domestic abuse, about all of the things that were going wrong in marriage that, if you watched Ozzie and Harriet, you'd never know about.

And that's been consistent through with TV is, like, people are violating taboos, telling outrageous stories, and then to some extent being punished by the audience for putting dirty laundry in public. So, I would say the first real reality stars in the way you're talking about were on the show, An American Family, which I write about in the book. And it was a documentary about a wealthy family in California called the Louds. The parents went through a divorce on the air, and it had Lance Loud, an incredibly charismatic guy who was the first gay man on television.

And when that show was made, it was a documentary, but when they became famous, when the show came out, people reacted to them as reality stars, which is to say, they hated them, they judged them, they loved them, they felt like they knew them, and they analyzed them as though they were text. And I think that that was, that was the beginning of this weird conundrum that I write about in the book, which is the shocking trauma of reality fame, where, like, in a flash, everybody knows you, you're recognizable in every street corner, but you have no future career or money, and people judge you for having been famous.

I'm not saying nobody ever deserved it, but I'm just saying, if you talk to a lot of these people, you might feel more sympathy for that.

[00:21:46] Carmen: Well, you know, that's fascinating to me. I'm going to have to think about this and digest it. Because I do… I'm not saying I've been judgy, but I've certainly come to believe that people, kind of, understand what they're getting when they choose these shows. So, I'm going to have to contemplate what you've been teaching me today, Emily, about what, about what people experience.

I think the phrase that you used that was compelling to me was, kind of, the Las Vegas analogy, like the house always wins, like no matter how prepared you are, no matter how much you think you know, no matter how much you think you're ready for this, the house always wins and it's going to find a way to deliver what it wants to deliver, no matter what your expectation is or what you hope to do.

[00:22:24] Emily: Yeah. I will say that my caveat is always, like, not all reality shows are the same. A lot of what I'm talking about here are shows that, you know, I think dating shows have a particular level of cruelty to them. And I've talked to a lot of reality producers for this book, and I would always ask them, I would say, “What shows do you love making? And what crosses your line? Like, what won't you do?” A lot of people said dating shows. And these were people who had done, like, torture shows, shark shows, starving shows, travel shows. Like, they would do all sorts of physical intensity, you know, shock and distress, but there was something about dating shows and the way that it stirs up people's genuine emotions that producers felt uncomfortable with. And also, you know, there's a lot of chaos on those shows. Like, just, after a while, some cameramen don't want to shoot people vomiting on the beach. It's upsetting.

[00:23:15] Carmen: That makes sense. You know, we hadn't talked much about, you know, what I feel like has happened from some of the reality shows that I would describe as a positive, not that I'm saying they're all negative, but that has this positive framing, the kind of democratization of the types of creators that you see on these shows. You know, I'm thinking of RuPaul's Drag Race and some other kind of images and people, marginalized folks who sometimes you wouldn't see on shows because the scripted shows hadn't found a way to be as diverse and be as open. Do you think that's one of the, you know, identifiable positive things that reality TV has brought us that maybe scripted TV hasn’t?

[00:23:54] Emily: Yes, 100%. I completely agree with that. The Real World, I have to say, was especially striking for this. And there are all sorts of critiques that people could make of that show. But I write about, you know, the most notable figure, you know, Pedro Zamora, on season three of that show. And one of the things I found fascinating about Pedro is, unlike the people who went on season one, who we were talking about knowing what you're getting into, like, they really did know what show they were making.

[00:24:18] Carmen: No, absolutely.

[00:24:20] Emily: Pedro did. Pedro wanted to go on The Real World because he was like, “I'm a Cuban American gay guy with AIDS.” He was already an AIDS educator. It was during a period when many people wouldn't have known anyone like him. There was nobody like that in the media, on television. And he saw that this was a platform that he could get on that would enable him to humanize and educate the population in a unique way. It led people watching the show to feel like they knew him. And in a certain way, they did, because he generously shared his charisma, and also kind of used his charisma explicitly, like on purpose, to change people's attitudes toward AIDS, toward gayness.

But yeah, RuPaul's Drag Race is an incredible show. And in the book, I trace the fact that the creators of that show who were Ru's close creative partners for years, like back to the ‘80s, Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, who run World of Wonder. They had known RuPaul since their days making, sort of, queer punk public-access television. He had also come up doing public access, queer, outrageous, theatrical stuff that was nowhere in mainstream culture. And for years, they wanted to make a reality show with him. And everybody said no.

Because even though I would say a lot of reality TV is very gay, in many ways, it has a lot of gay creators, having a Black drag queen just someone like RuPaul, like, RuPaul became famous, but RuPaul's fame was always treated as this niche thing. And from their perspective, they were like, RuPaul should be the biggest star on Earth.

And honestly, it took the creation of earlier shows ranging from, you know, like, Survivor and The Real World, and then later on, you know, especially Bravo with Queer Eye, Project Runway, and shows that sort of opened the door a bit for queer representation to allow them to finally get green-lighted for that show.

[00:26:25] Carmen: There's a part of me that, you know, often, as a woman of color, oftentimes I'm concerned about how television shows Black folks, shows those images, how the global world sees Black folks through that lens. And I guess I'm asking, you know, because of Trump's start on The Apprentice, how you think reality TV has shaped the global perception of American culture.

[00:26:49] Emily: I mean, for one thing, I should say that reality television didn't just come from America. And a lot of the big shows that people are familiar with are part of a European boom that I described in the book, but couldn't possibly cover in a whole way. There's lots of countries that are left out of the book. But you know, like, Survivor and Big Brother all came from Europe.

As far as representational stuff, I mean, this has been an enormous issue within reality TV. As much as I talked up how Pedro Zamora transformed things as a Cuban American gay guy with AIDS, I mean, there was, there was a bunch of, as again, in scripted television as well, a bunch of baked in bigotry and, you know, both purposeful and accidental stuff that happened, some of it because of the design of reality TV. A lot of the early shows that were meant to have diverse casts ended up having one or two Black cast members. So, like, you know, when I talked to the two Black people who were on the first season of Survivor, the people making the show may have thought they were making a diverse show, but the Black people on that show knew that they had an added weight that nobody else on the show had, because there were not a lot of Black people on TV, and because they were in the minority in the cast, it altered… they were aware of their perception, they were aware of themselves as, like, representing Blackness. Certainly, for many Black men that I talked to who were on early reality shows, all sorts of images of, like, the angry Black guy and of the, of the outsider within the house and all of that kind of stuff, you know, haunted and inflected their portrayal from the beginning. And this has become a big issue in a period way past the book, because certainly, after the Black Lives Matter movement, whatever happened in the last five years, those are responses to things that have been going on for decades.

I tried in the book to represent the range of perspectives that people had because, of course, not everybody thinks of it the same way. It's not like there's one Black reality experience or anything else. But that persistent issue of being, you know, the one or two people in the house and being hyper-aware of the fact that a lot of the producers are white.

[00:28:58] Carmen: And I think you said something that was important, this weight of what you represent. And then back to our original conversation of not really knowing what to expect and what you get being edited in all these ways, then the tropes come out the, the standard perceptions of women and people of color and whoever it is that you feel like is not fully represented or fully fleshed out, come to be.

[00:29:21] Emily: Especially because casting people cast stereotypes. So, the idea of certain kinds of Black guys, of swishy, funny gay men as comic relief, the idea of, you know, sluts and bitches, like, they cast characters, and a lot of the characters reflect social ideas. This is not sophisticated stuff. I mean, this is just baked into the world. But the world is reflected in reality production. I will say, because we were talking about The Apprentice, Donald Trump was elected because of The Apprentice. The Apprentice rebranded him and convinced people that he was a genius businessman rather than a con man, a criminal, shyster, and racist. Like, he's… and in the first season of that show, he had a white guy and a Black guy as the final two people on the show. And he, you know, a producer, Bill Pruitt, who was on the show, and he's talked about this before, but he said that Trump used the N-word during the final conversation. And a bunch of people from The Apprentice talked to me very openly about this.

The thing is it's very grim to think back on for a lot of them. And I was very interested in their perspective on, how responsible do they feel about the rise of Trump? This, you know, who did racist and sexist stuff on the show that everyone just laughed off, ignored, or edited out of existence. And the truth is, and I don't think this is uncommon, the higher you go on the call list of the crew, the more ambiguous people feel and the lower people really own it. Like, they're like, “We did this. We caused this.” Like, they feel guilty about it. I mean, there's a variety of attitudes, but at the time, I think a lot of people that I talked to were just like, “We thought he was a clown, but it seemed like a comedy.” Like, it didn't seem like a big deal.

[00:31:03] Carmen: But I want to stop you for a second, Emily, on that, because you would think the reverse would be true, that the, kind of, higher up the food chain, the more they would feel responsible for it.

[00:31:12] Emily: No, it made their careers. It made their careers. Like, they're not going to be like, “Oh, I did something bad.” Like, they also, you know, honestly, you know, it's so funny. Bill Pruitt has this great quote in the book where he said, “People work just as hard on shows they sell their souls for.” And that's the truth.

Like, the first season of The Apprentice, in particular, you know, I rewatched it for the book, it's a very entertaining series. And actually, in a superficial way, it actually seems really progressive because it's like, it's like a fantasy version of Wall Street where it's a race and class-diverse meritocracy that's half women. Like, it just seems like it's this version of Wall Street that treats it as creative as ballroom dancing. Like, that's what the show is about. It's about treating marketing and money and Wall Street and capitalism as something where anyone could make it if they just work hard enough and get Donald Trump's eye. Like, that's the fantasy that's expressed on the show.

But also, it's a well-made show. There was a lot of money behind that, a lot of skilled people working insane hours, coming up with, kind of, clever schemes. It's a… and it has great characters. It wasn't an accident that it was a success.

So, when you say, why couldn't they take responsibility and feel ashamed? Well, they would have to denounce their own work, much of which they feel proud of. And I say this in the book, but it's the dark irony of Trump, which is this: It's one thing to take a mediocre businessman and make him look a little better; it's another thing to take a multiply bankrupt joke who was basically like a sitcom walk-on during the ’90s and turn him into somebody that people think is such a glossy, impressive figure, that he's like the best businessman in New York and the country and can be president. In a sick way, that's actually quite a marketing accomplishment. And that's what The Apprentice did. So, let's put that blame where it actually should be put, which is on Mark Burnett, who created that show.

[00:33:10] Carmen: Yeah, absolutely.

[00:33:11] Emily: I mean, at a certain point, the buck stops there. And he is responsible for the artistry of that show, and he is responsible for the incredible damage that it did.

[00:33:21] Carmen: But you know, for me, I mean, someone like Mark Burnett, I don't think he feels bad about it because I don't think he feels that way about Trump. I assume he values Trump and feels like Trump is, is an asset.

[00:33:31] Emily: They’re very close friends.

[00:33:33] Carmen: So, one of the things that we haven't talked about, we've talked about some aspects of reality, I'm assuming that you think, kind of, cooking shows and the British Bake Off and all these things, kind of, fit in this genre, right?

[00:33:43] Emily: Yeah, absolutely.

[00:33:43] Carmen: You know, these, these shows. And I'm a big British Bake Off fan. Like, I love, I love that show. And I love it in part because, you know, the fact that you can be so intensely captivated by someone baking scones. I just think it's, you know, kind of, funny, on some level. But there's also a part of me that loves it because the kind of prize is a cake plate, right? And that's, you know, people are striving for this designation. But what they're really striving for is their colleagues’, sort of, view of their baking, something about it that seems maybe purer to me than some of the others.

But I guess I'm wondering, you know, on the whole, when you think about reality television, is this a positive addition to the way we see ourselves and view ourselves? Is it, is it negative? Like, what would be your final judgment, even though we say we’re not going to be judgy? Or, do you not think about it that way at all?

[00:34:39] Emily: I write criticism all the time. I write reviews where I say whether I think things are good or bad. That's not what this book is. This book is an attempt to take a thoughtful look at reality. And it is very much not one of those things where you can say, “thumbs up, thumbs down.” And to me, it's, it's significant. It's powerful. It's affecting. It clearly has both positive and negative effects.

I was talking to someone before, who was like, “it's a floor wax, it's a dessert topping, it's both.” I mean, I've talked to people who found it slightly more positive and people who found it slightly more negative, or people who were really disturbed by it. And it's been a little varied, which to me, is a positive suggestion, because the main thing I'm trying to be about reality TV is clear-eyed. And I'm trying to give people information about it, because I think, in general, people see it through a fog, which can be a fan fog or it can be a disgust fog.

So, that's my, that's my somewhat evasive but honest answer to, like, I can't say. And also, like you, I mean, there are shows that I love. Like, part of the reason I wrote the book is that I watched a lot of these shows, even ones I was ambivalent about.

But yeah, some of my favorite shows are shows that celebrate creativity. When Project Runway came out, and Queer Eye, actually, the first version, I was really excited about those shows. So, like there's shows that are celebratory of people's gifts and skills and, sort of, humanize various kinds of artistry in a way that I think is beautiful. But honestly, there are shows that are more like soap opera shows or shows that are adventure shows that, you know, I might have mixed feelings about elements of them, but sometimes there are moments on an unscripted show that you would never see on a scripted show that have such a force that, even if you disapprove, it's undeniable.

[00:36:28] Carmen: It’s undeniable.

[00:36:29] Emily: And that's the thing. I think that even people who disapprove of the, of the genre need to wrestle with, is that there's a reason why people watch, and it's because it's powerful.

[00:36:38] Carmen: Wow. Well, that's so, that's so great, Emily. I have to say that, just in preparing for this interview, you know, I was talking about this show I watch, called Blown Away, which is about these glassblowers. It's a competition show of glassblowers. And, you know, it was an art form that I… I got a chance to travel to Venice when I was really young, relative to where I am now. And I remember seeing it through that artistic lens when I was 14. And so, now, watching the show, watching these glassblowers compete, it's like, I love watching that show and enjoy it. And, you know, in some ways, I think one of the things I think is interesting about reality television a little bit is that, I found that when you talk to people about it, the shows that they really love, they don't really put in that genre that, that much. You know, they talk about it some other way. You know, “It's a competition show. It's a…” you know.

[00:37:32] Emily: In my book, I call it reality TV because that's what people call it. But everybody in the industry calls it “unscripted television.” They call it unscripted programming, which is like this anodyne term. But I think you're right. You know, the way that we were talking about, if you loved a TV show a long time ago, you had to be, well, it's really a 10-part movie. It's actually more of a novel. So, similarly, like, if you watch a reality show and you love it, you have to be like, “It's not really a reality show. It's actually a brilliant competitive documentary.” I love talking to people about what they're watching because there are shows I've never heard of. The glassblowing show sounds great, so I should check that out.

[00:38:04] Carmen: Yeah, it's called Blown Away. I don't remember what streaming service it's on, but it's just a fun way to watch a different type of artisan, you know, do their work in a way that, you know, you don't get when you're walking down the street. So, I think all of us, at the end of the day, we know we love aspects of reality TV, we, kind of, whisper it undercover, depending on when whoever's asking you about it. And then you have these moments where you're really frustrated by it.

Oh, Emily, this has been an awesome conversation. Uh, there's so many things we could have gotten into. But this is the last one, Emily. So, if someone asks you to create your own reality TV show, what would be the focus?

[00:38:42] Emily: College presidents on liberal arts campuses.

[00:38:47] Carmen: That one would… I don't know, I don't think that would go very far, Emily.

[00:38:52] Emily: You know, you take the cameras where the drama is, and I think that that would be an excellent plan.

[00:39:21] Carmen: Thanks for listening to Running to the Noise, a podcast produced by Oberlin College and Conservatory and University FM, with music composed by Oberlin professor of Jazz Guitar, Bobby Ferrazza, and performed by the Oberlin Sonny Rollins Jazz Ensemble, a student group created to the support of the legendary jazz musician.

If you enjoyed the show, be sure to hit that Subscribe button, leave us a review, and share this episode online so Obies and other folks around the world can find this. I'm Carmen Twillie Ambar, and I'll be back soon with more innovative thinking for members of the Oberlin community on and off our campus.

Running to the Noise is a production of Oberlin College and Conservatory and is produced by University FM.