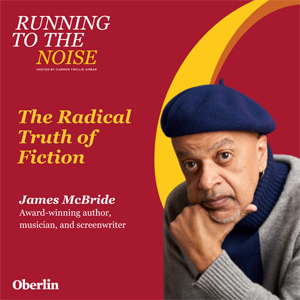

Running to the Noise, Episode 3

The Radical Truth of Fiction with James McBride

New York Times bestselling author James McBride took a circuitous route to becoming a great American novelist. A communications major at Oberlin College and Conservatory, he also studied jazz with Wendell Logan, the influential founder of Oberlin’s jazz department. After graduating in 1979, McBride went to Columbia Journalism School, then onto bylines in the Boston Globe, Rolling Stone, the Washington Post and People magazine.

New York Times bestselling author James McBride took a circuitous route to becoming a great American novelist. A communications major at Oberlin College and Conservatory, he also studied jazz with Wendell Logan, the influential founder of Oberlin’s jazz department. After graduating in 1979, McBride went to Columbia Journalism School, then onto bylines in the Boston Globe, Rolling Stone, the Washington Post and People magazine.

McBride left a successful career in journalism to “pursue happiness,” as he puts it: playing sax full time in New York. But his life took another turn when he penned a memoir about the person he loved most. The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother became an “instant classic,” in the words of one reviewer, and an accidental author was born.

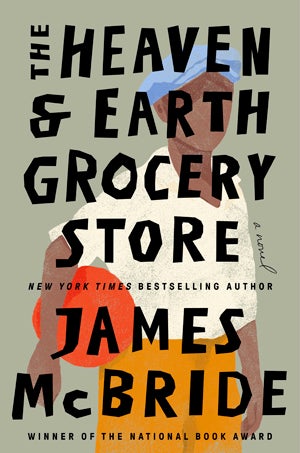

In this episode of Running to the Noise, McBride—whose new book The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store was recently named Barnes & Noble’s Book of the Year—joins host and Oberlin President Carmen Twillie Ambar to discuss his writing process, the path to authentic creativity, and the pursuit of happiness through art.

In this episode of Running to the Noise, McBride—whose new book The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store was recently named Barnes & Noble’s Book of the Year—joins host and Oberlin President Carmen Twillie Ambar to discuss his writing process, the path to authentic creativity, and the pursuit of happiness through art.

About James McBride

James McBride is the author of Deacon King Kong, a New York Times bestseller and Oprah’s Book Club selection; the National Book Award-winning The Good Lord Bird; the American classic The Color of Water; the novels Song Yet Sung and Miracle at St. Anna; the story collection Five-Carat Soul; and the James Brown biography Kill ’Em and Leave. The recipient of a National Humanities Medal and an accomplished musician, McBride is also a distinguished writer in residence at New York University.

Listen Now

[00:00:00] Carmen: I'm Carmen Twillie Ambar, president of Oberlin College and Conservatory. And welcome to Running to the Noise, where I speak with all sorts of folks who are taking on some of our toughest problems and working to spark positive change around the world and on our campus. Because here at Oberlin, we don't shy away from the challenging situations that threaten to divide us. We run towards them.

Reading a novel about James McBride is like listening to great jazz — you don't know what's coming with each turn of the page, but you can be certain it will be unexpected and often breathtaking. It's like nothing you've ever read before. It's no surprise McBride is a gifted saxophone player. He once turned his back on a successful career as a journalist to move to New York to play jazz and starve, as he put it.

He paid the rent by taking every kind of gig you can name — weddings, bars, dances, clubs. He taught English to Polish refugees. And he wrote music for everyone, from Anita Baker to Barney, the Purple Dinosaur. His story, of course, took one of those zig-zag turns of which he is so fond, when he started writing about the most interesting person he'd ever known, and the person he loved the most, his mother, Ruth.

Born in Poland and raised in Virginia, she fled to the South at 17. She landed in Harlem, founded a church, was twice widowed, and raised 12 children. Despite hardship and poverty, Ruth sent McBride and his 11 siblings to college. And McBride chose Oberlin. He penned a memoir, The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother, in hotel rooms, airports, and buses, while playing sax with jazz legend, Jimmy Scott.

That was the riff that made James McBride a full-time writer. The book was an instant classic. It has sold more than 2.5 million copies and has been translated into 16 languages. McBride has won two Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards, known as the Black Pulitzer Prize, an honor bestowed on the likes of Toni Morrison and Martin Luther King, Jr.

He's also won a National Humanities Medal and a National Book Award for The Good Lord Bird. That irreverent take on the bloody exploits of abolitionist John Brown, was turned into a Showtime series starring Ethan Hawke. His most recent novel, The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store, is receiving similar accolades.

In her review for NPR, Maureen Corrigan said, “As he's done throughout his spectacular writing career, McBride looks squarely at savage truths about race and prejudice, but he also insists on humor and hope.” I caught up with James on Zoom the other day when Barnes & Noble had named The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store Book of the Year.

So, what you heard a little bit of is actually by a friend of yours. Bobby Ferrazza composed that music.

[00:03:55] James: Okay.

[00:03:55] Carmen: And he's a professor of jazz and guitar, for those folks who are listening to this podcast. But it's also played by the Sonny Rollins Jazz Ensemble.

[00:04:05] James: Oh, great.

[00:04:06] Carmen: It's a little infectious piece of music. It actually reminded me of the last time I saw you, because the last time I saw you, I was in New York City.

[00:04:13] James: Yeah. Well, you came in, you know, deep into the hood. I thought that was pretty impressive. I didn't get a chance to talk to you that much, but…

[00:04:22] Carmen: Yeah, and saw our students performing and working with students.

[00:04:27] James: It was a middle school in Sunset Park. It was wonderful because most of those kids there, I'd say, maybe 75% of the schools speak Spanish at home. And they really loved what the Oberlin kids did. I thought the Oberlin kids handled themselves with great, great maturity.

[00:04:44] Carmen: Just so the audience knows about James, he connected us to Sonny Rollins, and out of that connection came the Sonny Rollins Jazz Ensemble.

And the whole purpose of that ensemble is, yes, to play jazz, but to also do what Sonny Rollins admonished them to do, which is that you can be a better musician if you are of service. It's something about being of service also allows you to be a better musician. And so, these students every year go to places around the country and they play jazz. And then, part of their time in New York City was to go and be of service. And one of the things they did was to go out to a school that James had recommended they go out to and help those students see jazz from a different perspective and see music played by people who are closer to their age.

[00:05:32] James: Yeah, you have to remember that some of the students, some of them have never seen live music before. Some have never seen an acoustic bass player play. Just the exposure to this is so, so important to a young person, because they were really enthralled with it. They were very quiet. They were wowed by it.

[00:05:50] Carmen: Yeah. You know, you forget sometimes, when you've had certain experiences, just how much that might be totally new to a child or a kid that’s never seen live music before, how much that can change your view of the world, just that opportunity to see somebody perform live.

[00:06:08] James: Well, I mean, it all speaks to the liberal arts experience and the liberal arts education. You can't be creative if you haven't seen creativity. Can't really expand your horizons if everything you see is from, you know, in an 8-inch telephone screen. A lot of those kids from Sunset Park and from Red Hook, their breadth of experience, even though they're in New York, they're not the type of kids you'd see at a Manhattan club. I mean, in fact, they're not the type of kids that would… they just don't venture past their neighborhood. So, this was a great experience for them. And that's really where liberal arts education begins, you know.

[00:06:46] Carmen: It's so fantastic. And I'm so excited to talk to you. So, I'm… I was telling people today that I'm feeling really smart today because we happen to be recording this podcast on the same day that Barnes & Noble named your book the best book of the year. And so, you know, if folks haven't been out there to get Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, then, You're missing it. You need to go and get it, because, you know, it's another James McBride classic.

So, James, what is your routine? So, when you have an idea, when that spark of creativity hits you when you're writing a novel, what is your routine? How do you go about the writing process?

[00:07:29] James: Well, I basically spend months and months and sometimes years researching.

[00:07:34] Carmen: Right.

[00:07:34] James: So, that means getting out, talking to people, going to places, you know. It doesn't matter whether, you know, if I have to go to a place. There's a difference between a McDonald's in Eastern Maryland and a McDonald's in Des Moines, Iowa. And you just have to figure out how to make that, you know, put that in your brain. Otherwise, you can't really smell the land, you know. You have to go there. You have to, you have to smell the land. You have to eat the food and you got to walk the earth, wherever you're writing about. You have to walk the earth, even if the earth is… that you're walking over is 200 years old from the time you started your story.

So, basically, I just do a tremendous amount of research. I'm always researching. Life is research. And then, at some point, you know, I have enough material to sit down and write. But I don't really write until, you know, the muzzle is fully loaded. Pardon the awful metaphor. But essentially, I just do a tremendous amount of research. So, I'm always researching two or three things at a time.

[00:08:36] Carmen: Or three ideas at a time?

[00:08:38] James: Yeah.

[00:08:39] Carmen: Interesting. So, when you're doing your research, is it about location first? Is it character-driven? You're trying to figure out how to think about a particular character? Is it all those things meshed together?

[00:08:54] James: Not really. I mean, you know, if you're talking about fiction, then, you know, you run into an interesting character in your imagination, and then you have to find a place where that character lives, but then you have to ask yourself, why do I like this character and what that character represents?

Because the deeper story of a book is what powers it. Once you get past the structural issues that a novel or screenplay or creative writing piece represents, you have to get to, why am I sitting down to write this, in the first place? And if you haven't figured that out, then there's no real sense in doing the project at all.

So, you have to look at writing in two ways. For a young writer, you know, writing is a kind of catharsis and a search for identity. Once you figure that out, then the tradecraft, which you can learn at a place like Oberlin, comes into play. And that tradecraft comes from, you know, the learning, labor, and discipline you develop as an undergraduate student who studies whatever you're interested in.

[00:09:52] Carmen: Right.

[00:09:52] James: The actual exercise of writing a book, I get up at 4:00, 4:30 in the morning. I write for as long as I can, which is usually, you know, 2 or 3 hours. And then, I... and the phone starts ringing and things that, you know, stuff starts clinging and clanging. And then, before you know it, it's 7:00, you know, PM.

But I usually do my writing really early in the morning. And then, if I'm working on anything involving music, I'll… I go through stages, I'll practice or whatever. Just so the students know that, you know, when I graduated from Oberlin, I went from Oberlin to Columbia and got a master's.

[00:10:30] Carmen: That’s right.

[00:10:31] James: And then, I went, worked at several newspapers and I quit all those jobs. I did that for nine years. Worked for, you know, People, Magazine, Boston Globe, Washington Post. That was the last job. And I quit that, and then I just played music for nine years.

[00:10:45] Carmen: Was that decision to quit, were you nervous about that? What was your mindset?

[00:10:50] James: Well, I wanted to be happy, you know. And I wasn't happy as a journalist. So, I just went where happiness was. I was happy playing music. I was broke, but I was very happy. When I was a sophomore at Oberlin, I went to Europe on a, you know, exchange program. And I, you know, I encourage students to do it. They don't do it enough, certainly. They should, but… and I met an old lady there who was… she was a survivor of the first and second world war. Her name was Madame Rouet.

I used to talk to her about my college life and what I was going to do afterwards. And she said, “I've always done what I wanted to do, and I've never been sorry.” And I had to look no further than my own mother to see someone who had always done what she wanted to do and wasn't sorry about it.

[00:11:33] Carmen: That's right.

[00:11:34] James: So, you know, if you're making decisions based on money, you're not going to be happy. But you have to be willing to struggle. And that struggle will inspire some kind of creative activity. And that creative activity usually brings a great amount of joy. If you want to be like… you want to have a steady, you know, steady job the rest of your life, well, you know, teaching is very creative, and it's wonderful, and you meet people, and you engage with young people who change your life. And that's one way of doing it.

But another way of doing it is to simply just decide that, you know, you'll do whatever you need to do in order to do your art, because your art makes you happy. That's, kind of, how it worked for me. So, I didn't really choose to be a novelist. It just rolled out as life, kind of, shoved me forward.

[00:12:21] Carmen: Wow. You know what I love about that James? There's so much debate on college campuses now about how to help students think about their life after Oberlin and their careers. And, you know, we try to do all these things to give them a framework for thinking about it, but you probably gave them the best advice, you know. Go do something that makes you happy.

[00:12:40] James: Well, I mean, look, when I was coming out of school, they used to say there are no jobs. Forget it, you're not going to get a job. I went to see Thad Jones and Mel Lewis playing in New York. And I was talking to one of the saxophone players, and I said, “How much are you guys making?” And he said, “We're making like, I would think it was $30 for the night.” And I was like, “Oh, boy.” I said, “Well.” And this guy was great. I said, “Well, I'm..”

[00:13:00] Carmen: Right.

[00:13:02] James: I might as well get my tin cup out and start begging right now.

[00:13:06] Carmen: If he's making $30 and he's fantastic, what…

[00:13:08] James: Yeah, right. What about me? But what happens is, if students can simply discard this whole business of you must leave school and work for Google right away and make $80,000 a year or go to Harvard or something, do something stupid, and not really enjoy your youth, you're making a tremendous mistake. The world is full of people driving BMWs living in gated communities who hate their jobs and are unhappy.

So, you know, you have to move to happiness. And it doesn't mean you should be poor.

[00:13:39] Carmen: Yeah.

[00:13:40] James: It does mean you should work hard, but it also means you should do what you like to do creatively. Because if you do it well enough, someone, at some point, somewhere, will pay you to do it.

The other thing to remember, I think, is that, the journey, I mean, when you're writing, the joy is in the journey. It's not in the… at the end of the journey. And the sum of your life is what you pay attention to. So, if you pay attention to these people who are going to school to become technical engineers to work at Google and, you know, sip latte and sit in Starbucks and look like they're writing novels, then that's how you're going to end up. You're going to be just like them.

You know, you got to be the person who walks past that Starbucks, goes to Dunkin Donuts and get a, you know, get a cheaper cup of coffee, and walk the neighborhood and see what people are talking about. Otherwise, you'll never, in terms of writing, you'll never write anything that's different than what the next guy does, or gal.

[00:14:36] Carmen: You know, one of the things I read about you when you were teaching writing, when you're teaching writing at NYU, it's like you send your students out to go in the city and go ice skating, go do something. Is that what you're trying to get them to do, just go and see something other than what they normally do?

[00:14:50] James: Of course, yeah! I mean, you know, I tell my students, the more I talk, the less you learn. You know, writing teaches writing. You have to go out and do stuff. Go ice-skate, you know. Go to Brooklyn, see where Ebbets Field was and write about power.

Go to, you know, go to the museum and see and find something that, what does the color red mean to you now? Find, you know, what is destiny? What is the word… you know, what is womanhood? I try to make them focus on writing structure. You can't write without structure, and you can't write without character.

So, I force my students to write about things that involve characters, real people, as opposed to like navel gazing, “I felt this and I felt that, and I felt this and my tooth hurt. And then, my phone rang. And the text came, and it was my brother from Minnesota.” And nobody went, that's blogging. That's, that's typing. That's not writing.

Writing is drawing oxygen from the room, knowing that you just… there's only a certain amount in that room for you, so you just get it in as much as you can and look around as fast and take your pen out and start scribbling. You know, put some action in everything. Let the action be outside of you and not inside you.

Now, you know, Oberlin has plenty for writing students to do. There are plenty of interesting students on campus, plenty of interesting things on campus. And there's plenty of interesting things outside of campus that students can engage in.

[00:16:15] Carmen: Right, all sorts of interesting places and towns and regions here and places for people to think and contemplate. Is that, you know, I've also heard about you that you don't have a television. I don't know if that's true.

[00:16:27] James: That's true, yeah. I don't have a television.

[00:16:30] Carmen: Is that also you not wanting to, kind of, clutter your mind with other people's stories, have that distraction, not going out to live and engage?

[00:16:37] James: Yeah, pretty much. I mean, you know, if my job is to create new stories, why do I want to hear what somebody else has done?

[00:16:44] Carmen: Mm-hmm. Well, I couldn't let you go without talking a little bit about Heaven and Earth Grocery Store. As I said at the beginning, it's won Barnes & Noble's Book of the Year. For those of you who haven't gotten this book yet, because you're late to the party, the novel begins like this murder mystery in 1972 with the discovery of a skeleton at the bottom of a well, and then goes back in time 47 years and introduces us to a rich cast of characters, African Americans, Blacks, and Jewish immigrants of Chicken Hill and Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Some of you know I used to live in Allentown, Pennsylvania, so not that far away.

And the genius of the structure of this book is that every major character that you're introduced to is a potential victim and a suspect. So, you're constantly trying to figure this out as you go along.

And, you know, James, you told the New Yorker that you wanted to have books that make you feel good about being alive, that you wanted a book that would take you to a place that you'd like to be. So, I guess, the first question about this book is, like, why Pottstown in 1925? Why would that be a place you'd want to be?

[00:17:47] James: I just happened to stumble into Pottstown when I was going to Pennhurst. Pennhurst is a mental institution-

[00:17:54] Carmen: Yes.

[00:17:55] James: … that was closed down. And I went out there and was snooping around there. And I saw a sign that said, “Pottstown.” So, I said, “Let me go to Pottstown,” because initially I was going to set this book in Pottsville, because Pottsville is further west. And it's near Pittsburgh, and Pittsburgh has, had, and probably still has a large Jewish and Black community. Pottstown was close enough to Philly. And when I started investigating Pottstown, again, I just did my boots on the ground research. I went to the library, went to the historical society, started talking to people. I found out there was an area there called Chicken Hill, where all the Blacks and Jews and Whites who couldn't afford to live better lived.

And so, well, I just dropped my characters in that place because I wanted to show what a small town was like, you know, during that time.

[00:18:44] Carmen: So, one of the things that happens in Heaven and Earth Grocery Store is that the Jews and the Blacks of Chicken Hill come together to try to protect Dodo, a 12-year-old Black orphan who's lost his hearing. And so, the social welfare types from the state want to ship him off to Pennhurst, this notorious asylum.

And I wanted to know, James, why were you drawn to write about such a place? What drove you to, to pick that type of place to spend some time writing about?

[00:19:12] James: Well, I mean, when I was at Oberlin during the summer, I used to work at a camp for handicapped, for so-called differently abled children. And so, when I started researching that particular character, I kept coming up with mental institutions, because in those days, in ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s, they sent these kids to mental institutions and they would have nothing. They have a simple case of cerebral palsy or something, they'd be in a mental institution for the rest of their lives. So, it was just… it was a death sentence, really.

So, I just decided to, you know, look into that and figure out a way to show that in a way that, you know, you don't want to write a whole book about that because nobody's going to read it. But I wanted to dip the oil stick in and let the reader see what some of these young people had to deal with. People with disabilities are, are very much like a Black person the South in the 1930s getting lynched where everyone gets to make a speech about you, but you.

And so, disabled people, so-called differently abled people, particularly children, are, you know, people have been talking over their heads all their lives. And I wanted to find a way to allow them to express themselves on the page without imposing my own so-called abled view of matters. And so, that's why I went to Pennhurst.

[00:20:31] Carmen: So, when you're writing a novel like this, are the... you know, I've talked to a fair number of writers. And sometimes, the characters are telling them what to do, like you, as you're writing, the characters are kind of driving you. Or, sometimes you'll talk to authors, and they kind of already know. They have the, kind of, end in mind. And so, they're just writing what they already know to be happening.

[00:20:57] James: I'm more of the former. I don't really know where a book is going to go. In fact, the back of this book, it got so complicated in terms of plot that, once I finished it, you know, I had to go back and... you know, once I write something, I hate the rewriting processes.

[00:21:11] Carmen: Oh, that's interesting.

[00:21:13] James: So, I had to go back several times and figure out why it happened like this. In this book, once Moshe, who's the Jewish theater owner, falls in love with his wife, their love powers a hole. It just pushes the thing all the way into Nate and Addie and their love.

And that love powers the book. The book is really about equality. At bottom, you know, murder, mystery, and all this, that, and the other. But the deeper story in that case is, it's about equality.

When I was working at this camp for handicapped kids, the person who ran the camp was named Sy Friend. This is in the ’70s. And Sy was a single man. He had to hide the fact that he was gay. He was, he was extremely smart. And he changed all of our lives. And the reason why he changed all of our lives, because he knew how to talk to his kids. He ran that camp. If you didn't care about those kids, you didn't last there very long.

The way he talked with those children was that he talked with them. He never talked down at them. He never had to command them. And they were kids, they would do kid things. Because he understood that, you know, they've experienced more than one fingernail worth of life than he had experienced his entire life. And he understood their wisdom.

[00:22:23] Carmen: Right.

[00:22:24] James: So, he always made sure they were treated as equals. He showed equality in the way he dealt with those children. And with all the characters in the book, there was a lot of equality in their relationships, because they were all pressed against the wall. They were all against it. Moshe and his wife were Jews in the 1930s. And small-town American Jews were, they were not welcome.

[00:22:46] Carmen: Right.

[00:22:47] James: Nate and Addie were Black. They were not living on the good side of town. So, they all had, kind of, a wall to push against. And that wall that they pushed against was what equalized all of them. And so, that's why the book is about equality, because, you know, Dodo the 12-year-old kid who the authorities want to take away, he kind of gives them all something rally behind.

[00:23:09] Carmen: Right, a singular purpose.

[00:23:11] James: But what they're rallying behind is they're rallying behind the idea of equality and justice. And there's a lot of ways to do it. One day, you know, you can pull out a gun and start shooting. Well, that's one way of doing it. You know, it didn't work out too good for Jesse James or none of them. But the other way to do it is to figure out, you know, how do we work around this in a way that is mindful and that is full of reason and discourse and that leaves everyone a chance and a place to escape to and still maintain their dignity and humanity?

[00:23:41] Carmen: Yeah. One of the things I find so interesting about your work is that I feel like you write really authentically for voices from a variety of communities. And it's interesting because you know this. We're, kind of, in a world right now where people are offended if you're writing, you know, something for a group that you're not a part of. You know, how can you write authentically for this person or that person? You're not Italian. You're not this. You're not that. And I'm wondering how you have come to that ability to be able to write different ethnic groups. I know you've expressed some concern about writing for women or writing as a… I've heard you say that before.

[00:24:19] James: Yeah. I'm not that comfortable writing from a woman's perspective. Because a woman's heart has many chambers of secrets. And, you know, I mean, how many can you get to before someone says, “You're a fraud?” So, I…

[00:24:34] Carmen: I don't, I don't know. Not that many, though.

[00:24:38] James: But, you know, anyone… listen, the music is out there to be played and listened to. Whoever is truthful, their music makes them free and the listener can connect. And the writing is the same thing. It doesn't matter who says it. If the words are pure, and the writer… you know, when James Baldwin writes about whatever he writes about, he comes from such a pure place. But when Paul Monette writes about who wrote… Paul Monette wrote a book called Becoming a Man during the AIDS crisis. And he was a great writer. He was just as pure. He was a little more raw, but he was just as pure and just as gifted, you know.

So, look, if it's real and it's pure, the reader will get it. And if, if it's not, they just want to read what they want to read, anyway. I mean, you can't place judgment on people. When there's judgment, there's no journey for them or for you. Placing judgment on a person's work is a mistake, because then, you know, I mean, if you don't like it, close the book. But, you know, don't, don't say, “I didn't, yada.” It's too much. It's just a lot. There's too much room for negativity in that sort of thing. No one's… you know, we're all human. That's the big thing.

[00:25:43] Carmen: It’ll be interesting to hear our students’ reaction to that and anybody who's listening to this podcast, because I do think that's part of what's going on right now, a kind of real judgment, lack of willingness to have anybody be in the space who's not from that community, from that perspective. Lots of judgment going on.

And it feels to me like one of the big things from much of what you write is a sense of our commonality, right? The things that we have in common as a way for us to think about the world, as opposed to… and you obviously show our differences and you're writing about different communities, but you also spend some time, I think, helping the readers get to a sense of what is common about us. And I think that's one of the things that's so appealing about what you write.

I couldn't let you go without two seconds on The Good Lord Bird, because if I don't talk about that, then my mom's going to get upset. And we don't want to make my mom upset.

[00:26:36] James: We don’t want that.

[00:26:39] Carmen: We don’t want to make my mom upset. I know I hear that you've credited Oberlin professor Geoffrey Blodgett's class on the Civil War and Abraham Lincoln with giving you a taste of history and storytelling. And I'm wondering whether that had any impact on you as you were thinking about this particular book. Well, you know, Geoffrey Blodgett was a professor at Oberlin at a time where, you know, we've always had our differences between Blacks and Whites on campus. You know, all that was going on, but everybody liked Geoffrey Blodgett. His classes were great.

He was just... he was such a gifted raconteur. He could really tell. He made history come. It's like going to the movies when you went to class. Talk about Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln had a wingspan of a seven-footer, and he was the greatest wrestler New Salem, Illinois had ever seen. I wish I'd studied more history at Oberlin, really, because of Geoffrey Blodgett.

But yeah, when I put The Good Lord Bird together, it was that business of, how can this character really come to life for the reader in a way that the reader will relate to? And of the things that was interesting about Geoffrey Blodgett was that he was funny. He was a funny guy. He told stories in a funny way, you know. He just had a sense of humor until, of course, it came time to take the test. Then, it wasn't funny.

[00:27:55] Carmen: And then, the humor was gone.

[00:27:58] James: You know, you've got all the jokes then. But so, I wanted the book to be humorous. And, and, you know, I know that John Brown had a history at Oberlin as his, I think, his father was an original trustee and one of his 19 men was the only college student when John Brown was an Oberlin college student.

[00:28:14] Carmen: So, he was a student who was paying for joining John Brown's ill-fated raid.

[00:28:19] James: Even though they executed him, they were sorry to do it. They said he was such a nice young man. I remember, I think, one of the prosecuting attorneys said that it's a shame that we have to execute this. He was a very, very kind person. And he was very dedicated to the cause of freedom and so forth.

[00:28:37] Carmen: Right. Did you know about that story before you left Oberlin? Or, did you discover that in your research?

[00:28:43] James: No, I discovered it in my research. I didn't know anything about John Brown when I was at Oberlin. I didn't… you know, I didn’t pay any attention. I wasn't the bald, mature, you know, smiling person you see in the dad and afro. I weighed, you know, 80 pounds. I didn't know. I didn't know what I was doing.

[00:29:01] Carmen: Well, I will say that that book, you know, taking this different approach to John Brown with this very humorous approach to a rather serious topic is one of the really interesting things about The Good Lord Bird. And so, you know, if you haven't had a chance to read that book, I don't know where you all have been if you haven't had. What's going on with you? You need to catch up on all the great things that James McBride has been doing.

I guess my last question for you, you know, you talked about pursuing a profession that makes you happy, not pursuing happiness, but pursuing a profession that makes you happy and wanting to read books that make you feel alive and that bring you joy. Given what's happening in the world today, you know, we're dealing with what's happening in Palestine and Israel, we are dealing with just, kind of, a feels like a relentless look at racial unrest, gun violence, how do you find that sense of joy and that sense of happiness when the world around you seems like it's not quite living up to that same spirit?

[00:30:06] James: One of the things I learned over the course of my, you know, 66 years is that you have to know when to stand up and when not to, and, you know, know what battle to pick and which battle to choose. So, you have to figure out where you're going to… if you really want to make change, then just be a healer. Be a healer of some type. I don't really participate in protests or anything like that. I try to make my little world work. My little world worked when you and Bill [Quillen, Dean of the Oberlin Conservatory] and Bobby Ferrazza and the Sonny Rollins Jazz Ensemble walked into that middle school in Brooklyn. Because, you know, my church and my community, we serve that, that school. We serve those kids. And that's the best I can do.

So, I'm interested in solutions and not… and so, I say, seek solutions. And because the demonstrations will come, and they'll go. And if you don't do something positive with your life, then those people who are dead with whoever they are died for nothing. So, I don't waste time with that, because it's not a waste of time. It's good to think about these things and discuss them in reasonable ways, but not, not in ways that will hurt yourself, especially when you're young. Because you take this stuff. So, you know, stuff is… so, you take it to heart. It's so deep. It's so real. And it is real. But most important is that you live long enough to do something about it. If you're young and you throw yourself head and head and shoulders into something that you don't really understand all the way, you can tend to hurt yourself and not help anyone.

[00:31:40] Carmen: Well, I have to say, you know, what we've been trying to say on campuses that, you know, at the end of the day, what we really can do on campus is to be in community together with each other and to be in dialogue with each other and that that's the way that we're going to change the world for good, that working on that community, and recognizing each other's pain, but also recognizing each other's humanity.

And I have to say, James McBride, that reading your books is one of the ways that we can recognize each other's humanity, because that's what you ask us to do, in all the twists and turns and shocks, and, “Oh, my goodness, what's going to happen here?” But at the end of the day, we are charged because of who we're reading about and what happens in their lives to recognize their humanity.

So, thank you for taking your time to do this. I really appreciate it. I feel great because I get a chance to go back and tell my mom that I got a chance to talk to James McBride. So, I get an A today, I think, from her.

[00:32:38] James: Well, I think you're well deserving of it. And, you know, I'm a big fan of you and all the things you've done for Oberlin. And, you know, once again, I can't say enough how much I appreciate what Oberlin has done for me and my family. And I wish the students all the luck in the world. And keep up the fight.

[00:32:55] Carmen: Thanks for listening to Running to the Noise, a podcast produced by Oberlin College and Conservatory and University FM, with music composed by Oberlin professor of Jazz Guitar, Bobby Ferrazza, and performed by the Oberlin Sonny Rollins Jazz Ensemble, a student group created by the support of the legendary jazz musician.

If you enjoyed the show, be sure to hit that Subscribe button, leave us a review, and share this episode online so Obies and other folks around the world can find this. I'm Carmen Twillie Ambar, and I'll be back soon with more innovative thinking for members of the Oberlin community on and off our campus.

Episode Links

Running to the Noise is a production of Oberlin College and Conservatory and is produced by University FM.