Postcards from Italy

Eli Goldberg ’12

It was the beginning of July. I was packing frantically, and emptying my inbox with equal fervor. In a bit over a day, I was leaving for five weeks of field work in Italy -- one of the perks of being an archaeology major. Five weeks in Europe! Five weeks of excavation and research! Five weeks with limited Internet access... how liberating!

And then this happened.

And so Ma'ayan and I began our transatlantic postcard-blogging experiment! In the process, I learned two important things:

1. Mail from Italy to the U.S. is slow and unreliable. (Hence, the reason you're reading this now instead of a month ago -- and one of the postcards was lost entirely, or is still wending its way across the Atlantic.)

2. It's hard to say insightful things on a small postcard, especially under the combined influence of archaeology, sleep deprivation, and limoncello.

But here, as best as I could capture it, is all the glitz and glamor of archaeological field work distilled into seven postcards...

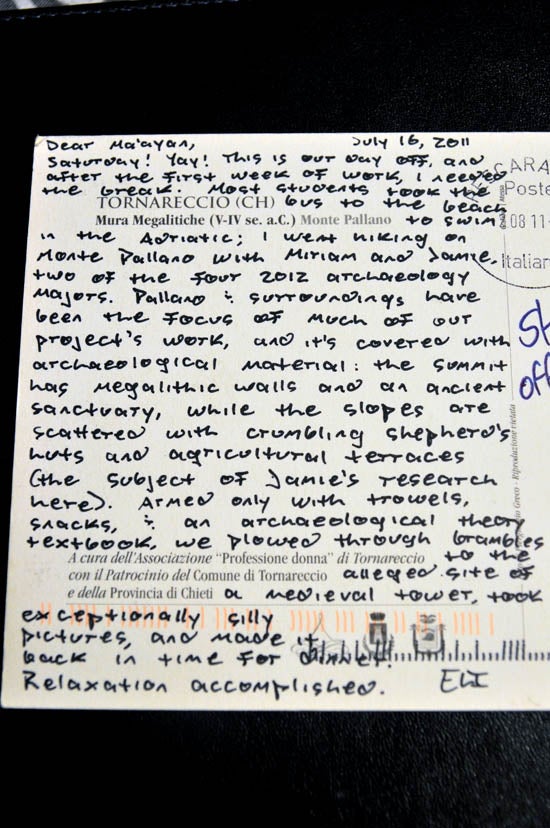

Dear Ma'ayan,

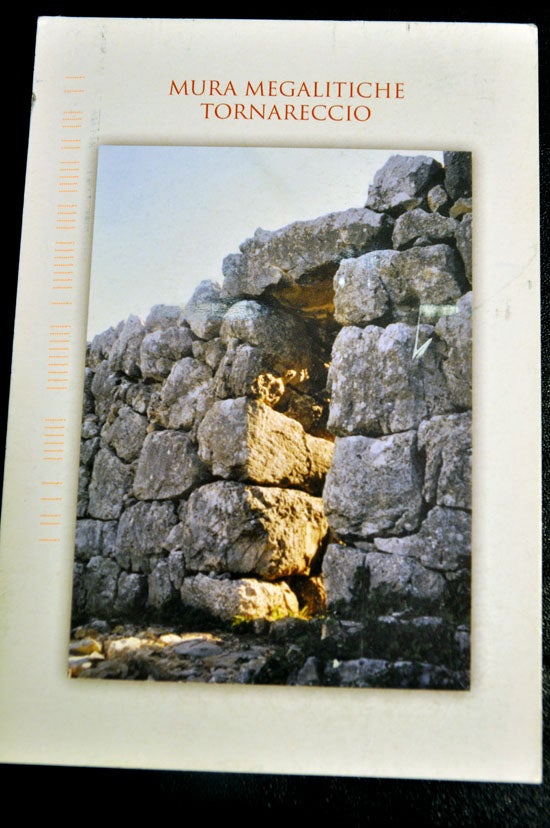

Well - it involved two days and three countries, a car, a plane, two trains, a bus, and another car, but I finally made it! For the next month I'll be here in Tornareccio, a tiny little town sandwiched between the Apennines and the Adriatic, which happens to be the home base for the Sangro Valley Project. A small crew of archaeologists have been here for the past week, but there's still a lot to do before the season starts. Tomorrow we start moving equipment into the local middle school, turning it into a makeshift laboratory and student dorm. For now, though, there are new staff to meet, old friends to catch up with, and a huge Italian dinner to eat!

Eli

Tornareccio: two thousand people, four bars, three churches, one gas station -- and, for a month or so every summer, a few dozen archaeologists. This is a part of Italy that most American tourists don't ever get to: close-knit, traditional rural towns tucked away in the mountains. Coming in as an outsider, it's a hard place to get a handle on -- and most of the archaeologists are definitely outsiders, set apart by language, culture, and history. The Sangro Valley Project is a collaboration between Oberlin and Oxford, and although we've been working in and around Tornareccio for nearly two decades (sleeping in the middle school, digging on the mountain, walking through farm fields in search of sherds), the annual influx of Brits and Americans still attracts attention, amusement, and probably no small amount of annoyance.

I first came here as a field school student in 2009, the summer after my first year at Oberlin, and it was easily the scariest thing I'd ever done. I'd been abroad before, but never for nearly this long; my Italian vocabulary was limited to musical terms, pasta shapes, and bastardized Latin; I knew practically nothing about the town, and practically no one from the project. After three years, it's familiar enough to be fun rather than terrifying. No way will Tornareccio ever become home for me, the way Oberlin did -- but I have a strange little relationship with this corner of the world.

Postcard #2 didn't make it back to Oberlin, but here's what it said:

This summer about four dozen staff and students rolled through the SVP at various times (getting everyone in and out of Tornareccio on time is a big deal.) As with any archaeological project, there's a definite hierarchy, and the farther up the pyramid you are, the less time you spend holding a trowel and the more time you spend doing paperwork and being a diplomat. At the top is Susan Kane, the project director and chair of Oberlin's Curricular Committee on Archaeology. (Hovering over her head is the regional archaeological superintendency, which gives us permission to do what we do.) Susan acts as the SVP's long-term memory, supervises everything and everyone, liaises with local government and friends of the project, and deals with crises ranging from "we can't find a site!" to "we're out of Ziploc bags!" Below her are staff managing excavation, field survey, computers, and lab work, and specialists who deal with everything from ceramics to seeds to ethnography -- not to mention the cook, who at the beginning of each season announces his firm conviction that "an excavation marches on its stomach!"

At the bottom of the ladder are the field school students, there to learn and to move dirt. Field school is a rite of passage and an essential career move for any aspiring archaeologist: it's the moment when you put down your textbooks, pick up a trowel, and discover how things really work -- sweat, sunburns, muscle aches and all. The SVP's Oxford students come from a rigid curriculum of nothing but classical archaeology, while the Oberlin students are about split between committed archaeology/anthropology/classics majors and curious ones just looking to explore, in true liberal arts fashion. Each year a few experienced students return to help supervise in the trench, or to work on an honors project, as I'm doing. I think of our roles in summer camp terms: if the field school students are the campers, we're the CITs -- definitely not staff yet, but experienced enough to know our way around.

Days of fieldwork are long. They start around 6 or 7 AM standing in line for breakfast, smearing on sunscreen, and hopping into a van to the site. They end with an evening lecture, an enormous Italian dinner (have I mentioned the SVP has great food?), and more often than not a night at the bar. What you do in between depends on who you are, what the weather is like, and what's happening at the site. As a field school student, you spend the first week learning to use the tools of the trade -- a trowel and a pick, a hoe and a malepeggio -- and rotating among the various specialists to learn how they work. Once you've seen a bit of everything, you get a chance to spend more time in the areas that interest you. On any given day you might be clearing off a building foundation in the trench, drawing and documenting artifacts, sorting ceramics, floating soil samples to look for seeds, or walking through fields in search of our next site. This is one of the things that fascinates me about archaeology: no matter what your skills and passions are, chances are they're relevant in some way, and there's a use for them on site.

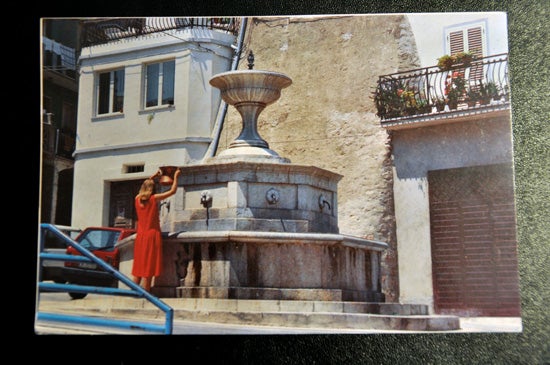

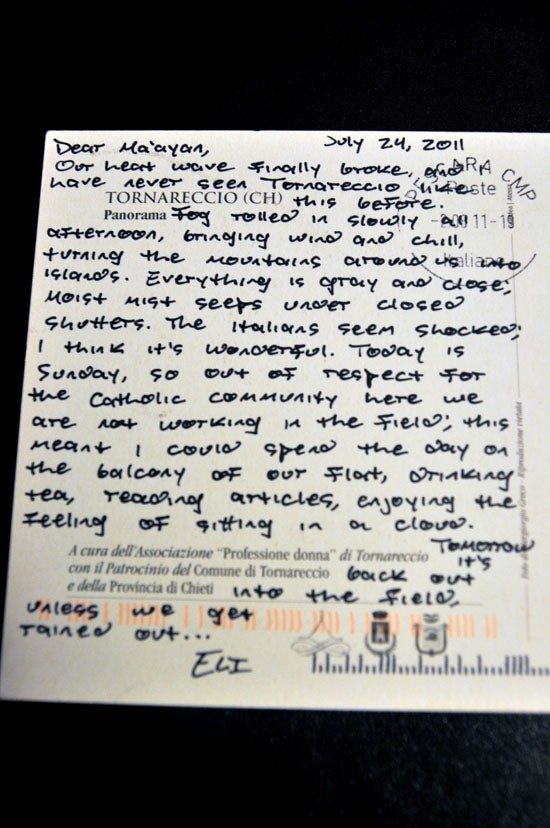

There are so many things I could write about the wonders of days off, but I think this picture says it all:

In some ways, archaeology is all about the unexpected. Despite the best educated guesses, you never really know how much you'll find until you start digging, and it can take a while to determine what exactly you've got. Your site is 300 years earlier than you thought; there are three buildings where you only expected one; you find a pit full of animal bones the day after the faunal expert leaves; the potsherds don't match the regional ceramic sequence. And you've only got a few weeks to figure it out. This is in addition to the logistical uncertainty of archaeological work: everything from weather to local and international politics can get in the way on a moment's notice. Things pop up, and you find ways to keep working, and adapt your theories as you go.

This year brought a few more surprises than usual. We were digging in an area we'd never worked in before, a family compound in the center of town, which came with a whole new set of local relationships and social expectations. As we worked through the site, locating a building and chasing down the foundations without much else to go on, theories flew: an early medieval church? A Roman bathhouse? The final story -- well, I'll let you know when it's published. Suffice to say that even on a relatively small site, archaeological interpretation is never straightforward; it's an exercise in keeping your mind open and flexible. As Miriam, one of the student trench supervisors, commented to me, there aren't many other jobs that require so much physical work, so much detailed observation, and so much intellectual creativity all at the same time.

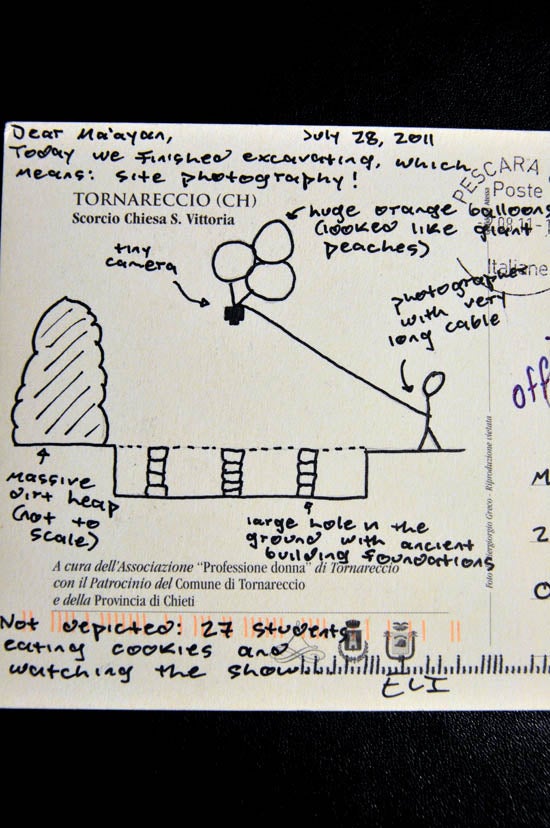

The end of excavation always takes me by surprise. This year we worked on-site for two and a half weeks, an unusually short season. Suddenly the digging was done, and artifacts needed to be labeled, nested in boxes, and carried off to storage; our makeshift labs in the local middle school needed to be dismantled; and the site needed to be backfilled. There's something bittersweet about seeing what you've worked so hard to excavate swallowed by soil -- maybe to be uncovered again the next summer, maybe to sit untouched for years, decades, centuries...

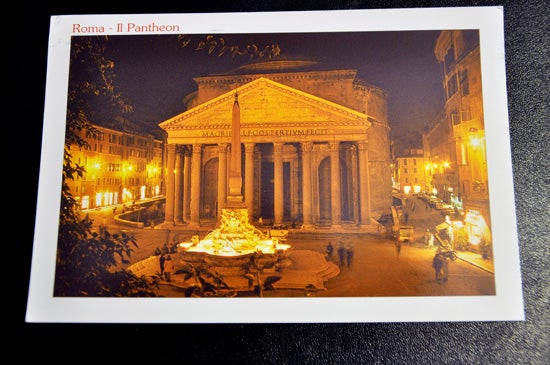

Here's the deal: there are lots of things you can do at Oberlin, lots of things to study, lots of research opportunities. But -- even with all the hard work and all the little frustrations -- I honestly believe I have the coolest major, and the coolest summer job, in the world. At least, it's easy to believe that when I'm sitting outside the Pantheon on my way home from the field: boots caked with ancient dirt, sleepy and sore and sunburned, watching tourists walk by and wondering what it would be like to do this every summer for the rest of my career.

And I made it home with the best souvenirs of all: new data and fresh samples for my honors project! But that's a story for another post...

A thousand thanks to Ma'ayan for being my correspondent and photographing the postcards for me!

Tags:

Similar Blog Entries

Ballad of the Witches' (Academic) Road

Games, music history, and queer theory — oh my!

Oberlin in Days Past, Pt. 2

Getting to learn more about Oberlin and Shansi in the early 1900s through the Mary Church Terrell Main Library’s Special Collections.